Although it is only about 12 kilometres from the centre of Jerusalem, Bethlehem is a world away – or to be more precise, it is in Palestine, and it involves a transit through the Israeli wall. And like our previous two visits into the West Bank, this third visit confirmed that the area under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority is indeed a very different place from ‘mainstream’ Israel.

Leaving aside the claims and counter-claims, it is interesting to speculate whether Palestine is part of Israel or not from a purely practical, or pragmatic, perspective. An article in this morning’s “Jerusalem Post” quoted an Israeli Government Minister as saying that Israel’s promises to uphold human rights within its territory clearly could not apply to Palestine because Israel did not have the authority over the area in order to be responsible for what happens there. And yet an article in today’s “Jordan Times” carries front page news about Israeli authorities demolishing some Palestinian homes near Hebron in the West Bank on the grounds that they were built without proper planning permission. Palestine does have a separate identity, its own flag, its own license plates for cars, and as we discovered today, it issues its own postage stamps, but it uses Israeli money and it is clearly under the control of the Israeli military. Israeli-registered cars can enter Palestinian territory, but Palestinian-registered cars may not enter Israel. By general standards, it is quite a murky situation.

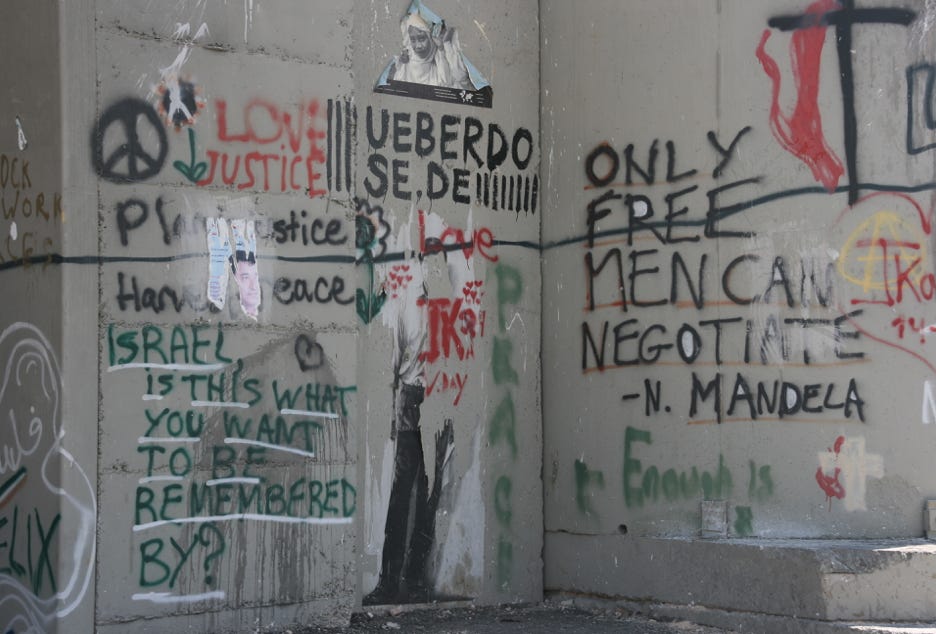

The separation barrier is a highly visible feature of Bethlehem today. One wonders whether Mary and Joseph would have made it through the scrutiny of the watchtowers if they had delayed their journey by a little over 2000 years.

And yet, having penetrated the wall, Bethlehem never ceased to delight. Unlike Nazareth, which has grown to become a bustling city, Bethlehem has somehow managed to retain its traditional character of an old Judean township. Even the presence of tourism has not spoilt the town’s character, although to be fair, Bethlehem has struggled to attract tourists in the last few years after violent clashes erupted some time ago between local Palestinians and Israeli forces. The local people, the majority of whom are Muslims, proved very gentle and welcoming, if at times a little over-persistent in their salesmanship.

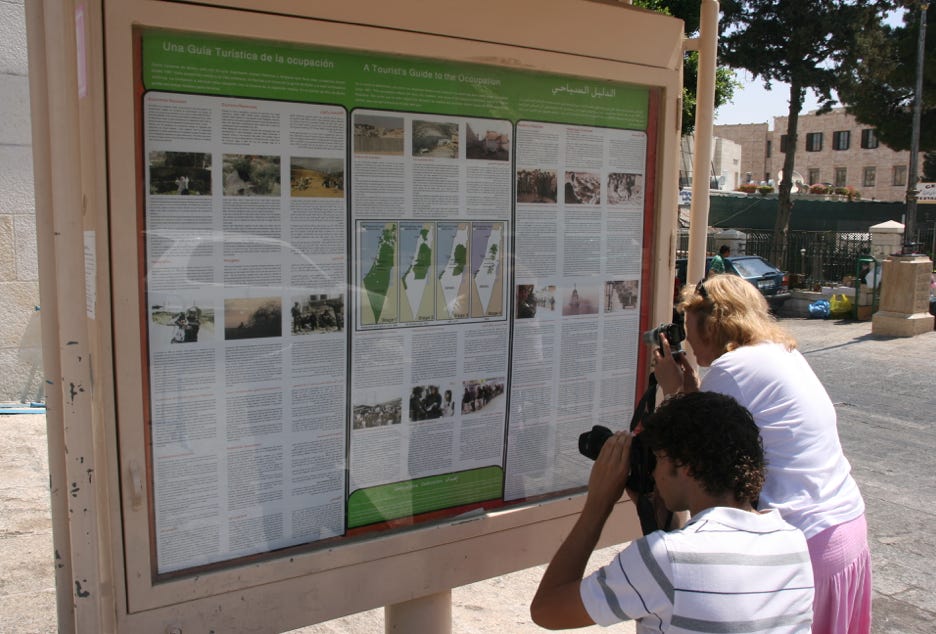

After a few brief photo stops, we drove through to the centre of Bethlehem, a hilltop plaza known as Manger Square. On one side of Manger Square was a large building labelled as the Peace Centre which contained a vivid display of the “Israeli occupation of Palestine”, including a very informative notice board outside with information and maps describing the situation from a Palestinian perspective. Maps purported to show in green the shrinking areas allowed for Palestinians to live and work, while white areas were said to be the expanding areas available for Jewish settlement. On reading the display it was hard to resist the comparison between the Roman authority over Palestine in Jesus’ day and the Israeli authority today.

Over to the eastern side of Manger Square was the Church of the Nativity, originally constructed in 326 AD and claiming to be the oldest continually functioning Christian church in the world. The present building was largely reconstructed by the Crusaders in the 12th century and is believed to have been built on the site of the birth of Christ, the main altar being directly above a small grotto which marks the birthplace.

The church was entered through a low door, known as the Door of Humility because of the need to bend over to pass through it. In fact, the door’s size has nothing to do with humility but it was reduced in size by the Crusaders as protection from invaders.

The main body of the church was a fairly dark and somewhat gloomy place, but a long line of people revealed the main centre of attention, the subterranean grotto marking the place where Jesus was born.

The grotto is very small, with room (just) for only two people at the time to kneel before it. The place where Jesus was born is marked by a 14-point metal star surrounding a sheet of glass beneath which is the rock-hewn place where Jesus is believed to have been born. As Jesus is regarded as a great prophet by Muslims (though not by Jews), the people visiting included some Muslims in addition to the overwhelming majority of Christians from all parts of the world (some of whom would have created a better impression if they had taken to heart Jesus’ teachings on meekness and patience).

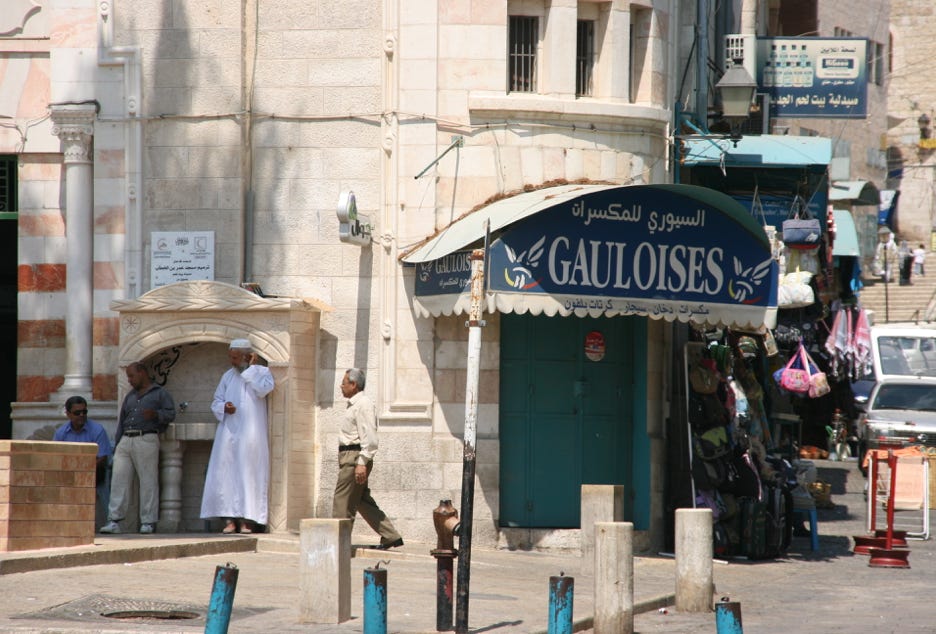

By the time we left the Church of the Nativity, Manger Square was really bustling with activity. Part of the reason for that was that Friday is the holy day for Muslims, and a large mosque that was situated on the far (western) side of Manger Square (the Mosque of Omar) was calling the faithful to prayer. For a while, the surrounds of the square were filled with Muslim men performing their Friday prayers. When the prayers had finished, we took a walk wound the narrow laneways of the old section of Bethlehem, although being Friday, the souqs and shops were uncharacteristically quiet.

As we drove out of Bethlehem towards the south, we were hoping to visit a Palestinian refugee camp known as the Dheisheh Camp that we had heard was a lively, welcoming and vibrant place. Perhaps naively, we were expecting the camp to resemble the small tented camps that we had seen in Jordan and Lebanon, but this camp was quite different. Rather than tents, the camp comprised two and three storey buildings, crammed together and constructed from concrete blocks. In the midst of the camp was a large three-part school run by the United Nations – a kindergarten, a boys’ school and a girls’ school, the last of these displaying some quite surprising street art.

We decided to drive further south to Hebron, described by the guidebook as the hidden jewel of the West Bank, but tragically troubled by recent outbreaks of violence (as today’s edition of the Jordan Times had testified). The violence probably explained the very tight Israeli security posts on the outskirts of the town, and was also displayed visibly by an overhead bridge with high concrete walls pitted by the bullets from machine gun fire.

In fact, we tended to find that Hebron had an elusive charm. Its historic city centre was dirty and run-down, except for one zone that had been taken over by (extremely brave, I suspect, or maybe just very well paid) Israel settlers, fenced off and guarded by multiple Israeli watchtowers. Di felt extremely uncomfortable in Hebron and just wanted to leave (which was easier said than done, as there was no signposting and very few exit points). She said the reason for her discomfort was that we only saw men everywhere, which was true – there was hardly a woman to be seen.

Hebron did, however, provide us with a great insight into the differences in living standards between Palestinians and Israelis, as can be seen by comparing the photos of Hebron with those of a nearby Israeli hilltop settlement that we also visited (Kiryat Arbaa).

I am leaving Israel with very mixed feelings. On one hand, I have been deeply impressed by the strides made by Israelis in economic development and the ‘greening’ of the desert environment; the Israelis have created a country with material standards that must be the envy of most other Middle Eastern countries. I found Israelis to be kind, welcoming and gracious people, which is also how I found the Palestinian people that I met to be. And yet, Israel is also a deeply troubled place, with the unresolved Palestinian question hanging over their heads like a heavy grey cloud. And that cloud probably seems even darker for the Palestinians. Any country that divides itself with high walls, watchtowers and barbed wire clearly has major issues requiring resolution!

In some ways, the Israeli-Palestinian question is a microcosm (but a very significant one) of many of the conflicts and tensions existing within the Middle East region. It has been a privilege to explore some of the tensions, the sights, the history, the geography, and especially the people, of some Middle East places over the past 29 days. My time travelling has been extremely stimulating but far far far too short.

I am leaving with the certain feeling that I must return!