I don’t think it would be possible to get too much further into the wilds of Africa than we did today without taking some fairly serious risks. We began the day without electricity (what’s new?) and without water (like yesterday); this was our second day without water which has made washing something of a problem. The owners of this 4-UN-car hotel did manage to get us a bucket of water to use, but unfortunately Andrew emptied 80% of it down the toilet within half an hour of arriving in our room in an unsuccessful attempt to ‘flush’ away his floater that he was embarrassed to leave there. Having thrown away most of our day’s supply of bucket water, and with no prospect of getting any more, we found that having to do all our body washing (for both of us) with the remaining two litres or so of water was a thorough (if odoriferous) challenge. The planned clothes washing simply didn’t happen. By the way, the hotel’s ranking was reduced today to 1-UN-car.

After a fairly plain breakfast of plain omelette, plain bread and not-too-bad coffee in the nearby hotel just down the hill, we left at about 7:30 am for our drive into Mago National Park. This involved a drive of about 3 hours to the west of Jinka, and a descent from Jinka’s 1200 metres altitude down to about 200 metres, where the weather was understandably considerably warmer.

The Lonely Plant Guide to Ethiopia sums up a trip into Mago National Park quite nicely, saying:

“Not for the pusillanimous, a visit to Mago National Park is a two-footed leap into true African wilds. You’ll battle roads that eat Landrovers for brunch, wage war with squadrons of mosquitoes and tsetse flies, and sweat more than you thought humanly possible. The payoff? It’s more adventure than you can shake a stick at! You’ll have the chance to visit Mursi villages along the Mago River and spot some animals too. One thing is for sure, you’ll never forget your time here”.

Yes, the road was very rough, and yes the weather was hot, but we didn’t see any mosquitoes (and we were definitely watching for them!). By law, we needed to have an armed escort accompany us. I asked, half jokingly, whether the armed escort was for wild animals or hostile people, and I was told “for hostile people, of course”, as though such a response should have been self-evident. Maybe that makes sense - after all, it is illegal to shoot animals in a national park! And I did notice that the list of regulations on the notice board at the entrance to the park included “No carrying machine guns” immediately below “No collecting wild flora”.

Our main aim was to visit a village of the nomadic Mursi people - presuming we could find one, because the Mursi people move camp every few months. As it turned out, we did find a village of unusually friendly Mursi people just a couple of kilometres beyond an abandoned encampment, and what a memorable experience it was!

The main activity of the Mursi people is raising cattle, which is why they are nomadic; they move according to the seasons. When they settle in one place for a while, they cultivate some sorghum, and we saw evidence of that this morning with cultivated fields beside the village compound, and some women were milling sorghum by hand while others were winnowing the seeds. Most of the people in the village when we visited were women and girls because the majority of the men and boys were away tending the cattle.

One of the unique features of the Mursi people is that women wear lip plates. These are made of clay and may be up to 15 cm in diameter. At about the age of 12, a slit is made between the lower lip and the jaw, and plates of increasing size are inserted as the lip stretches. The lip plates are not worn all the time, and many of the women we saw this morning were walking around with their lower lips swaying around below their jaws.

There are various theories as to why the lip plates are worn. Some suggest that it was originally a way of discouraging slave traders from stealing the women, because they generally wanted unblemished girls for slaves. Another theory is that it is done to prevent evil entering the body via the mouth. Yet another theory is that it is a sign of social prestige. The real origins of the practice are probably lost in antiquity, and these days it is simply an accepted, universal social custom among Mursi women. Our visit to the village this morning did nothing to shed light on the practice.

After we had spent quite a while at the village (I was enjoying myself so much that I didn’t notice exactly how long we were there), we left for the return trip uphill to Jinka. On the way, we saw several examples of wildlife, including kudu, miniature gazelles, harriers and several groups of baboons.

But the highlight was seeing an elephant, something that was so unusual for the middle of the day that our armed escort almost wet himself with excitement. And what an elephant it was - it was far larger than any of us had ever seen before, with very long mammoth-like tusks and huge ears. As we approached, it walked off into the scrub at the side of the road, where it began attaching a tree, almost completely uprooting it. Just as we were preparing to get the perfect photograph, it noticed us, snorted loudly, screeched, and started charging. I have never seen an armed escort run so quickly, so we naturally followed his example, running for life’s sake back to the relative safety of the 4WD.

We returned to Jinka for lunch, which was vegetable soup like last night (it is the only kind of soup they offer), followed by spaghetti for me (same as last night) and injera with lamb for Andrew. After lunch we relaxed for a while in our room, hoping in an unfulfilled way that the water might be turned on so we could flush away the putrid smell permeating into our room.

We had heard that there would be some traditional dancing by the Ari tribe on the outskirts of town at 4:30 pm this afternoon, so we made the trip there. Apparently someone had forgotten to tell the dancers – this is literally what we were told had happened - so there was no dancing to be seen. We therefore thought it might be interesting to have a look through Jinka’s museum, which gets a reasonable write-up in the guidebook. We arrived there at about 5:00 pm, and although the advertised closing time was 5:30 pm, the curator had gone home for the day and everything was in darkness.

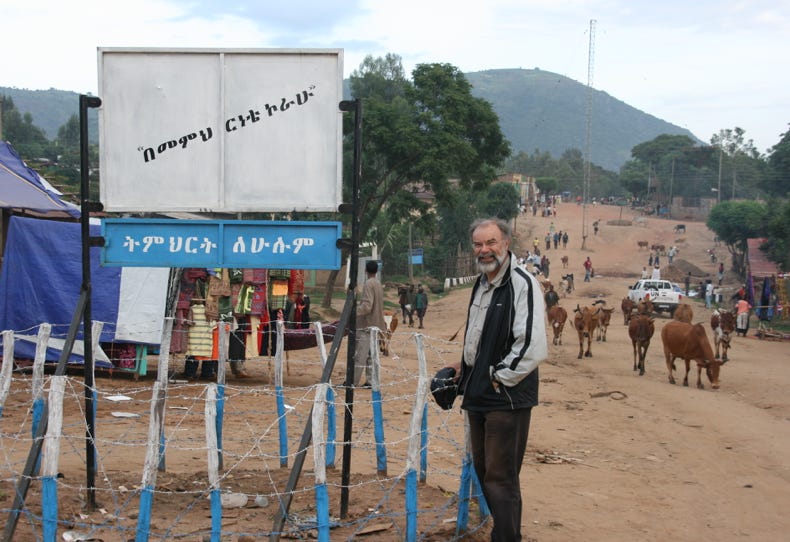

Therefore, we decided to walk back to our hotel, taking the long way round that passed through the market. This was probably more interesting than either the dancing or the museum would have been, and even though it was not market day (which is Saturday), there was a lot of activity and many things to see. Jinka’s streets are dusty, but being bright orange dust, picturesque in their own sort of way. I was especially impressed to see a sign at a small roundabout (yes, such things exist in Jinka!) proclaiming ‘Education for All’ under a larger sign that read ‘I am proud to be a teacher’. This is clearly a town with its priorities sorted out!