Neither Andrew nor I slept very well this last evening, probably for three reasons – the room was hot (never falling below 28 degrees, no aircon, and the ceiling fan stopped for 5 hours during the scheduled blackout), the pillow was rock-hard and our tummies were over-filled with couscous.

So it was little trouble to get up when the alarm went off at 5:30am, ready for breakfast at 6:15 and departure at 7:00am. Actually, this breakfast wasn’t too good – some dry bread with jam and some instant coffee with powdered milk. Andrew and I were both quite thirsty, so at extra cost I ordered a can of refrigerated pineapple juice for each of us, and it was the highlight of our breakfast.

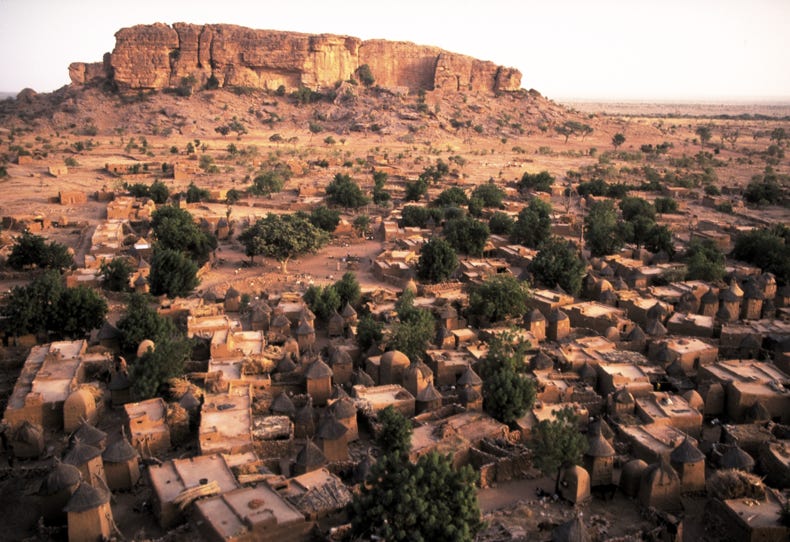

Heading off at 7am, our destination for the day was several Dogon villages, where we could experience the unique culture of the Dogon people, who inhabit the Bandiagara Escarpment, a 150 kilometre long sandstone cliff that extends in a north-east to south-west direction between the main part of Mali and the Burkina Faso border region.

Our first stop was a cliff-top village named Bongo. This was bit of an anti-climax. The focus was a cave filled with handicrafts for sale, and the end of which was a group of children who sing (somewhat half-heartedly and certainly out of time and out of tune) to welcome visitors to the village and then demand 100 CFA francs (about 25 cents) in return.

From the cave, you emerge to some extensive onion fields, which are an interesting example of cultural contact – cultivation of onions was introduced to the Dogon people by the French during colonial times, and they now provide the main source of income for the Dogon people. However the women cultivating the onions seem to resent visitors with cameras in their hands, even if the cameras are not used, screaming what I can only assume is abuse (judging by the tone) and throwing water on passers-by (actually, only small quantities of water, which Andrew and I found refreshing despite the aggressive tone with which it was done).

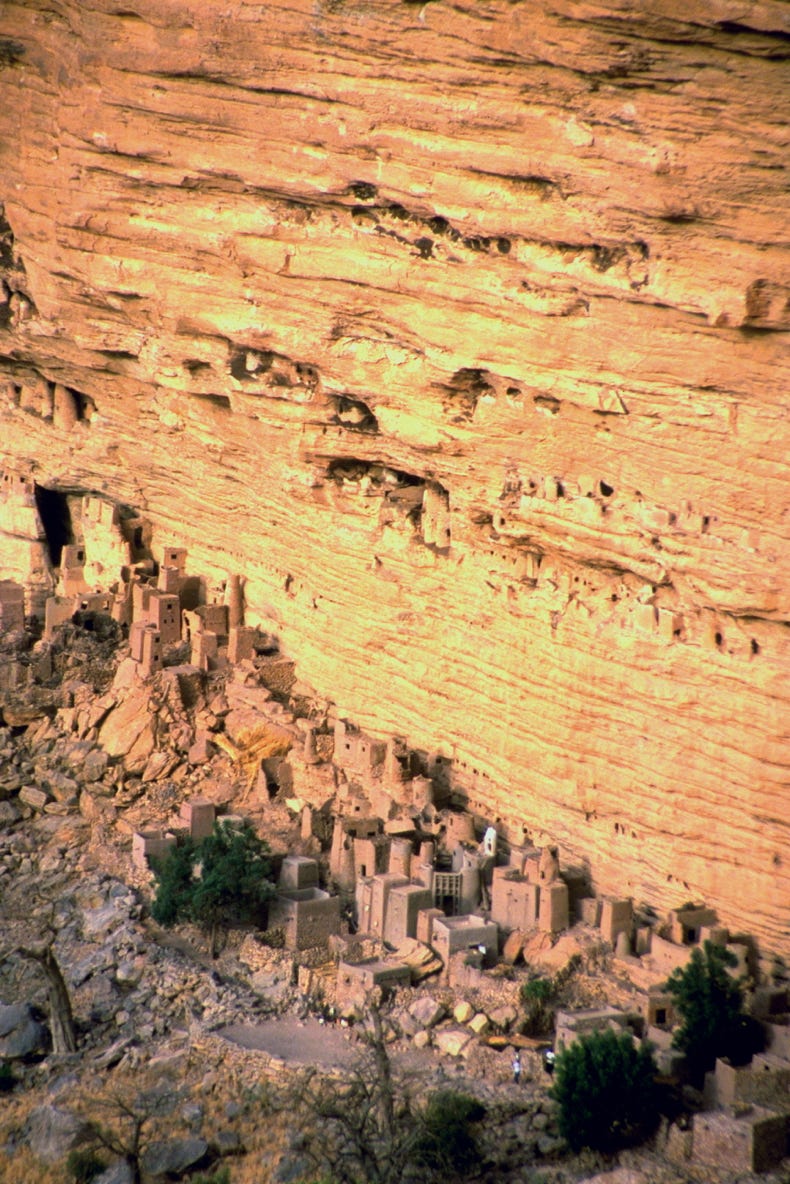

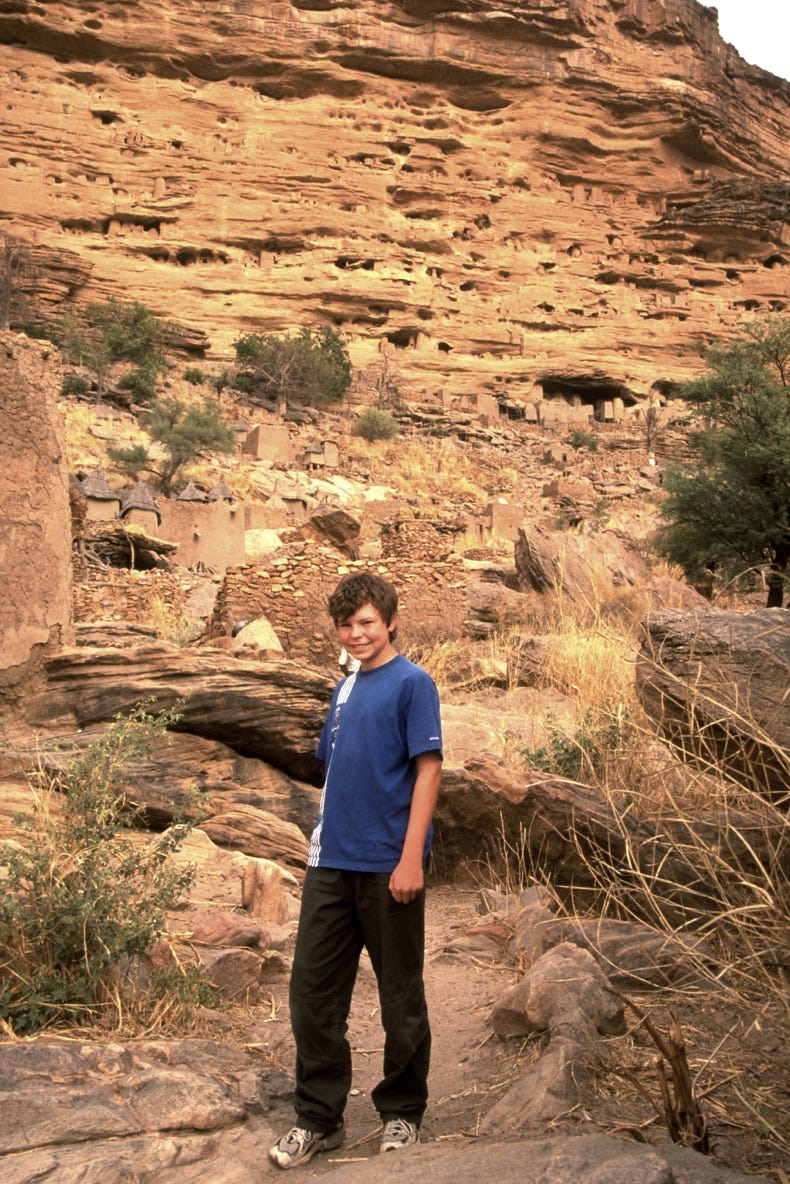

Not a great introduction to Dogon Country, we then proceeded right to the edge of the escarpment and descended down to the more typical villages. Our main visit was to a village called Ireli, which was fascinating. From a distance, the village is almost invisible because the houses look like the scree that has fallen down from the escarpment above. But upon closer examination, the form of a village emerges from among the rubble – a dense network of mud brick houses interspersed with small storage buildings called gran stores (which actually store all of a person’s valuables), topped with distinctive conical straw roofs if owned by a male.

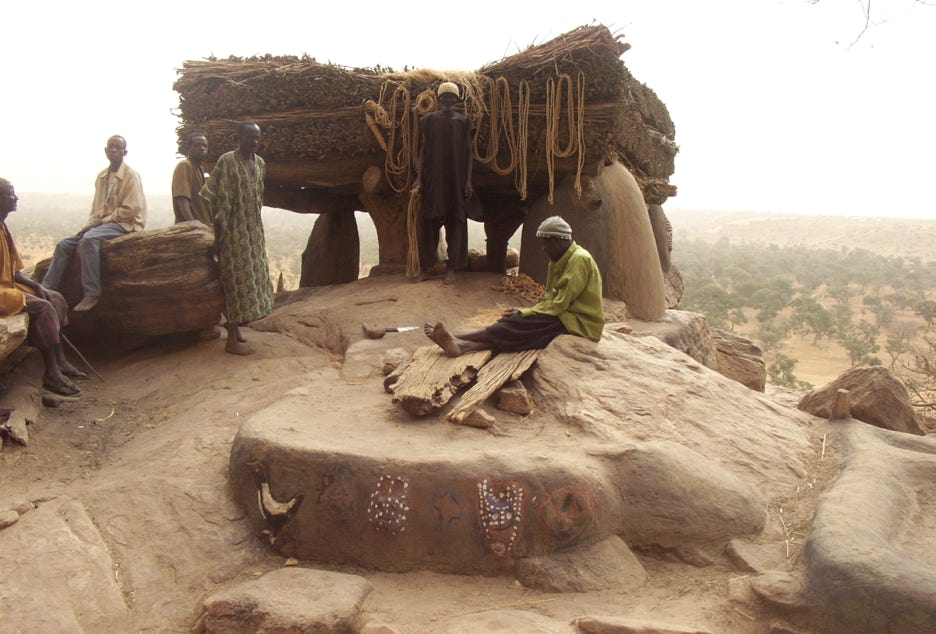

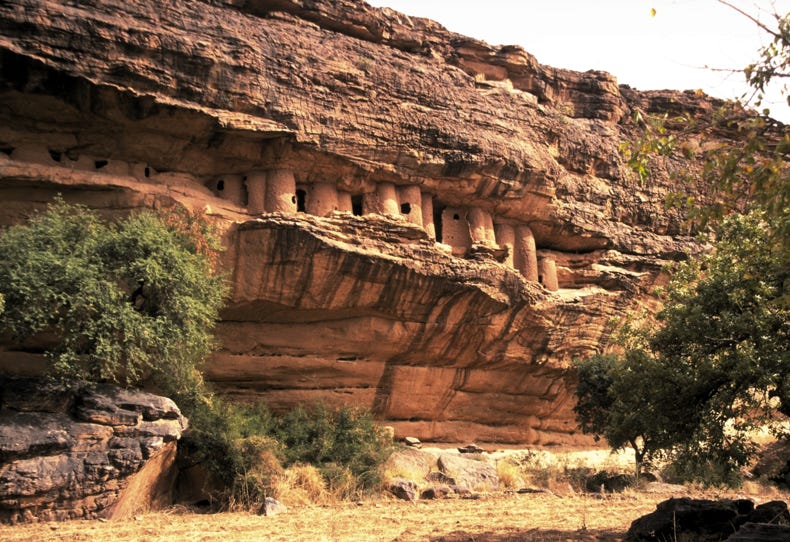

Like all villages, Ireli contained a fascinating meeting place structure, where disputes are discussed and arguments resolved among the men seated under the roof. The roof is deliberately very low so that no-one can stand up, and this prevents physical fights. On the escarpment above Ireli were the remains of an earlier society that inhabited the area before the Dogon. These people, the Tellem, lived half-way up the escarpment in what can only be described as positions of amazing defendability. The Tellem people have long been gone, and their houses are now used by presumably highly energetic Dogon people for fetish storage areas, and as collection points for bird droppings that can be used as fertiliser on the onion fields.

After Ireli, we travelled further along the foot of the escarpment to another village, Tireli. This village, which was Christian (unlike Ireli that was Muslim), seemed better developed than Ireli, though less traditional because of this. Although the grain stores were still made from mud bricks, many of the houses were built from stone and the village seemed a little more substantial.

Our main purpose in visiting Tireli was to experience a Dogon face mask dance. Although we had quite a long wait (about an hour and half), it was a fantastic experience when it happened. The costumes were very elaborate and full of meaning, which was explained to us by the village chief at the end of the dance. It was a great privilege to experience this event in the sacred village centre; fortunately in spite of most Malians’ opinions (or so it seems), Andrew is a male, because women are not permitted to enter the village centre. The dance was an experience not to be quickly forgotten – a visual and musical sensation.

We got on quite well with the village chief, an interesting man with two wives and thirty dependents. He told us that the women in the village all wanted Andrew to stay with them, and never leave, and after the dance he gave us lunch of ‘tô’ (pronounced dough), which is a grey-green millet paste accompanied by a green sauce made from baobab leaves, eaten with the hand (the right hand only, of course, because the left hand is reserved for that ‘other’ purpose). Both Andrew and I agreed that the tô was tasty good food.

From Tireli, we re-traced our steps a little and paid a short visit to Amani village to see the sacred crocodile pool. The Dogon see crocodiles as a sacred animal (even those Dogon who are Muslims or Christians seem to retain the animist beliefs), and the crocodiles are never harmed; in fact, they are fed by the villagers, and for this reason never seem to attack anyone.

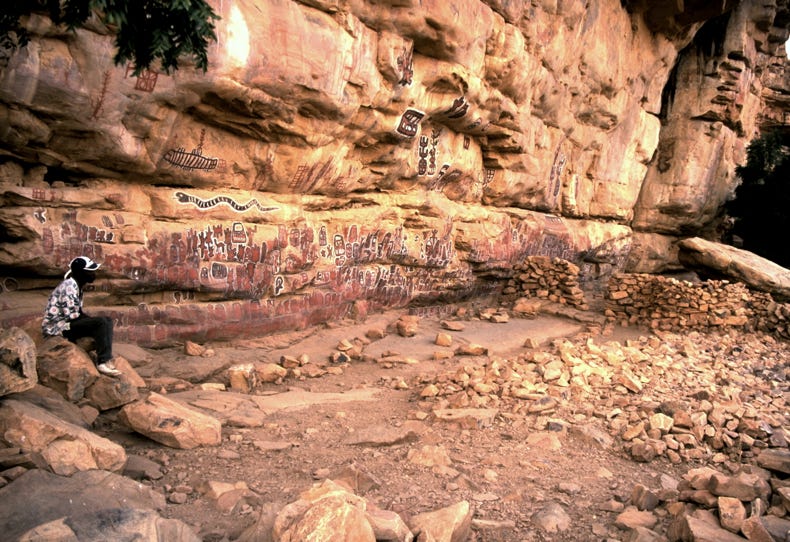

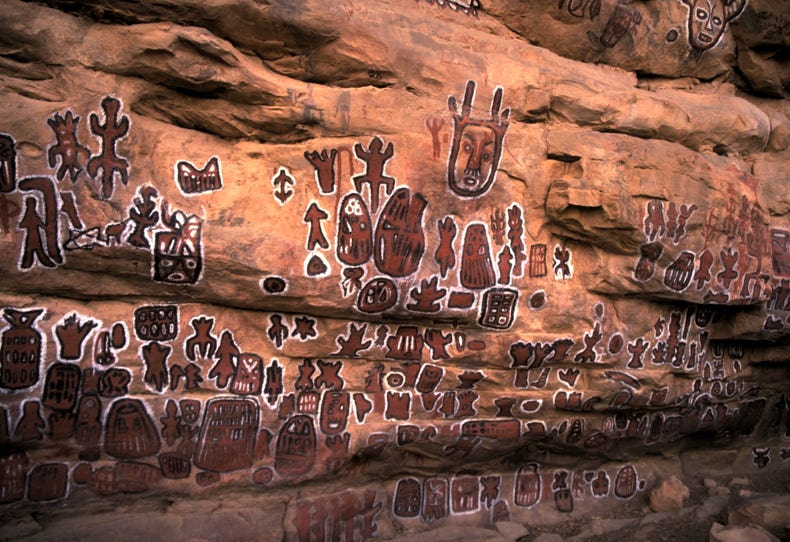

Having re-ascended the escarpment, our final visit was to Songo, the village we visited briefly the previous day but left because Andrew’s camera battery had failed. This was an interesting place in many ways, but the main reason for the visit was the circumcision grotto. This hollow in the cave of the escarpment is used once every three years for a circumcision ceremony, each of which initiates about 60 boys and young men (ages 8 to 16 or so). We saw the grotto, the musical instruments that are used, the rock under which naughty initiates are held, and we heard the entire story of the circumcision process – it was fascinating.

A local village person was explaining everything in French while I translated for Andrew, but I must confess that I reached the limits of my French vocabulary as he began explaining the details of the circumcision ceremony; fortunately Sory was on hand to lend some insightful assistance. The visit finished by climbing up the rock above the grotto to get a stunning panoramic view of the village. I am fairly certain that this was Andrew’s first ever visit to a circumcision grotto, and despite looking a bit intimidated from time to time (I guess a twisted facial expression suggests being a little intimidated!), he seemed to enjoy it. Maybe he was afraid that, like so many places in Mali, someone would be there and offer me a ‘special price’ that I couldn’t refuse!

The Songo visit concluded our stay in Dogon Country, and we returned by car to Mopti, staying once again in the same hotel that we have used twice previously for single night stays (where Michael Palin also stayed!). Unlike our two previous stays, we ate dinner at the hotel in Mopti this time, a lovely three course dinner of onion soup, diced beef with butter spaghetti and chocolate mousse for dessert. It was a long day, especially given the poor sleep the previous night, but an enormously enriching cultural experience.

This was not a night to catch up on sleep, however, because the next day was another 5:30am wake-up, with a 7am departure for the long drive back to Bamako, ready for the 3:25am departure to Casablanca with the connecting flight to London. But first things first.

Andy (age 12) writes:

Tuesday the 20th of January: Today I discovered why people here often think that I’m a woman. Dad said the reason must be that I’m as tall or taller than all of the fully-grown men here. The difference is that my voice hasn’t broken while they think that I’m far older than I am because of my height. Hooray! I don’t look like a girl!!! Well, last night I did not sleep well. I was awake from 12am to 5am when the hotel’s generator wasn’t turned on. It was very hot there and the only way that I could sleep was to have the fan on. It wasn’t the best breakfast apart from the fact that dad and I each had 500ml of pineapple juice. Soon afterwards, we drove to Bongo, which is a place where you get out at one side of a natural tunnel through a rock at which there are some tourist stores with some children there attempting to sell you some really crappy pictures that they drew with apparently no effort. They then run off to the other end where they form a choir of about 25 people to sing you a song in French to welcome you to their village. You’re then supposed to pay one of them about 100 francs (about 25 cents). When we were walking along through a farming area just outside the tunnel, a woman thought dad took a photo of her farming. She then ran after us splashing water on us from the big bowl on her head. I didn’t even do anything! We then drove to the top of the escarpment where we looked out over the remains of some Tellem people who had made their home in the holes in the cliff face. After dad had taken some more photos in the ‘great lighting’, we continued our drive and came to a village called Ireli. We saw many interesting things here such as their meeting place that has such a low roof that the people who go in must crawl. The idea is that you can’t stand up to fight. We also had a good view of hundreds of Tellem houses in the cliff. The next village we went to was called Tireli. Here, the main thing we saw was a very elaborate mask dance. Dad and I were the only people apart from the villagers to watch, which improved the experience. There must have been about 15-20 people doing the instruments with another 20 doing the actual dancing. The clothing for the masked dancers was very elaborate. There were also people there on very high stilts still dancing. Dad and I have photos that can show it far better than I can explain. Finally, we went to a small pool where crocodiles live. The people here worship them and regard them as sacred. You can walk right up to them. We then drove to a village called Songo. We walked around the town and up onto the escarpment which is where the circumcision grotto is. We learnt quite a bit here about how the children here become adults and some of the competitions that are held here when the 60 or so children are circumcised with one quick swipe of a knife by the head of the village. They then have to spend a week on the cliff and then 3 weeks in the bush. If they do something wrong then they have to sit in an enclosed space for about half an hour before then climbing over a very sharp rock while being whipped. After this we continued the reasonably short drive of just 30 km to Mopti where we are staying in the same hotel we always do in Mopti.