The second top photo to the right shows our view from the hotel window when we awoke this morning. Looking down across the Orontes River to the An-Nuri Mosque and its adjacent ‘noria’ (water wheel), bathed in the golden glow of the morning sunlight, it was simply magic!

Our aim today was to visit two places near Hama that were each distinctive in their own ways. The first destination was Crac des Chevaliers (or in Arabic, Qala’at al-Hosn), a hilltop castle built by the Crusaders in the mid-12th century.

The second destination was Apamea (or in Arabic, Afamaya, spelt in at least five different ways on various signs), a 2nd century AD Roman city. As there was no public transport to these places, we hired a little yellow taxi for the day, leaving the hotel after breakfast and a phone call at 9 am.

The drive to Crac des Chevaliers took about an hour and a half, including stops at an ATM for some much-needed cash and at the bus station to buy the tickets for the following day’s trip north to Aleppo. The drive took us to the south-west of Hama, just north of the border with Lebanon.

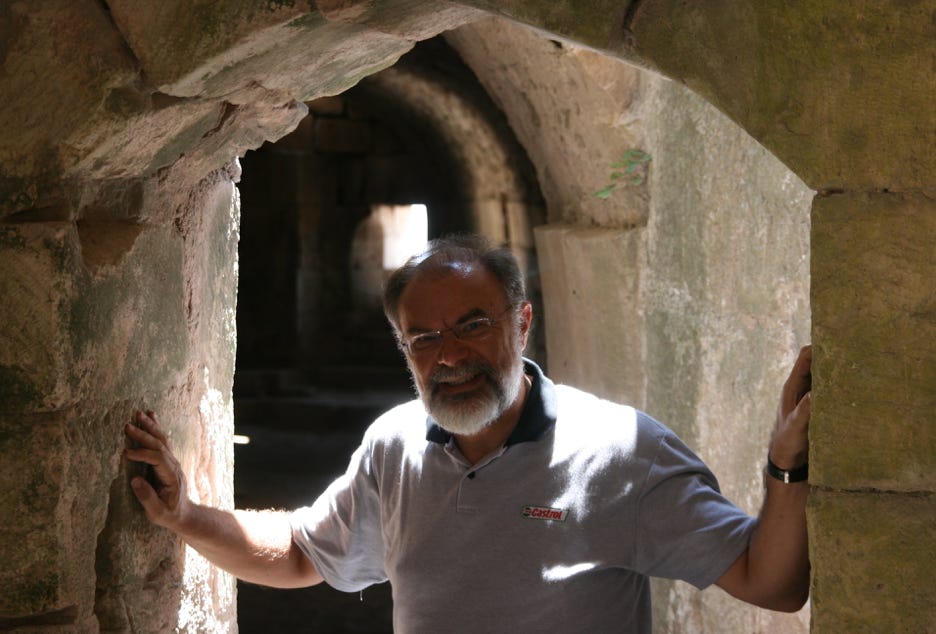

As soon as we arrived at Crac des Chevaliers, we could see that this an even more impressive castle than the one we had visited in Jordan at Karak. Entry into the castle took us along some inclined winding tunnels, illuminated only by some tiny open skylights, past large rooms that had been used as stables for horses, and across a bridge that spanned a moat separating the inner from the outer castle areas. The outer castle is the defensive perimeter, while the inner castle is a much higher complex behind it.

The castle was certainly substantial and built to last, which it has done, for about 850 years so far! It was great fun exploring the various corridors, rooms, stairs, turrets, walls and enclaves, guessing what some of the areas may have been used for in the Crusader era. The area that I enjoyed the most, and found most impressive, was the part known as the ‘loggia’, a long corridor with a Gothic facade that could have been found in Medieval Europe more easily than in Syria.

We finished our exploration of the castle by venturing up to the top, where several towers provided panoramic views across the countryside that the castle was designed to control, as well as the nearby small towns that gave us glimpses into the normal everyday life of Syrian people today.

At a little after midday, it was time to drive to our second destination, Apamea. This involved a drive of a little over an hour in a northerly direction, roughly parallel to the cost of the Mediterranean Sea but about 10 or 15 kilometres inland. We didn’t see the Mediterranean, but it was obvious that we were not far from it by the (relatively) less sparse vegetation and the cooler breezes we were experiencing.

Apamea (pronounced ‘Ar-fa-may-ah’) is described, somewhat obscurely, in the Lonely Planet guidebook as being “like a condensed version of a pink-sandstone desert city, but executed in grey granite”. Most of its temples and other buildings fell into ruin centuries ago, but its main thoroughfare – known as the “cardo” - was still very impressive. About two kilometres in length and forming a perfectly straight line, the cardo was originally lined by colonnades of pillars topped with lintels of carved stone. Many of the columns, most of which were erected in the 2nd century AD, were decorated with a twisting fluted design that was unique to Apamea.

Interestingly, anyone who visited Apamea as recently as 50 years ago would not have seen the lines of columns that we saw today. Most of the pillars and lintels had collapsed and lay around in pieces, overgrown by vegetation. However, a team of Belgian archeologists has been working at Apamea since the 1930s, and they have embarked on a program of what is termed “restorative archeology”, which means re-erecting the columns from the scattered piles of stone.

The result was extremely impressive, even if some imagination was required to visualise the city in its Roman heyday. Most of the structures had been reduced to their foundations, although at least that meant the baths (being dug below the surface) were relatively intact.

Apamea was considerably larger than Jerash which I visited a week or so ago in Jordan, and it had far fewer visitors. As a result, there was a real sense of exploring a ghost city when visiting Apamea, providing a true opportunity to reflect on what the city must have been like before its destruction. I had never thought of myself as being the kind of person to enjoy Roman ruins, but Apamea was breathtaking for its scale, grandeur, layout and reconstruction – a truly memorable experience that was well worth the effort to get there.

We returned to Hama and farewelled our yellow taxi driver at a little after 4:30 pm. Dinner this evening was an unexpectedly wonderful event. We walked to a little open air restaurant near our hotel called “Le Jardin” that overlooked the mosque and water wheels that we could see from the window of our room at the hotel. We had a wonderful view of three water wheels, one of which was right beside us, as well as the old mosque. Our waiter was amazing. Despite not having a word of English or French, he escorted Andrew and me down to the river’s edge to see the water wheel at close hand, showing us the interior of the building where the axis of the water wheel was loudly droning its mournful way through its rotations, taking our photos beside the water wheel, and explaining as best he could using sign language its workings.

And yes, the meal was great too; I had grilled “chicken cordon”, Andrew had ‘chick kebab”, we shared a beautiful minted hummus (more commonly spelt ‘hommus’ in this part of the world), and finished the meal with sensational ice cream and double shot Nescafés made on milk. The final finishing touch to a memorable dinner was seeing the lights come on across the river to illuminate the mosque and the water wheels. A restaurant with this atmosphere, location and service would cost a fortune in many places around the world, but our meal was just a few dollars.

There was just one irritatingly humorous incident. It is the custom at Syrian restaurants to place on the table a small box of tissues with the restaurant’s name emblazoned all over it so that one’s fingers can be wiped at the end of the meal, a courtesy for which an item labelled ‘tissues’ is routined added to the bill. Typically, the amount in question is 15 Syrian pounds (about 30 cents). Of course, you are free to take away the unfinished box of tissues with you when you leave. You can see our unopened box of tissues behind the Pepsi can in the photo on this page.

As I had already been accumulating surplus boxes of tissues in my luggage, Andrew and I agreed that we would not need to use any tissues at this meal. Sensing that this was so, towards the end of the meal, our enthusiastic waiter made a special trip to our table, opened the box of tissues, and withdrew one each for Andrew and me to use.

I am now carrying one extra box of tissues in my luggage.