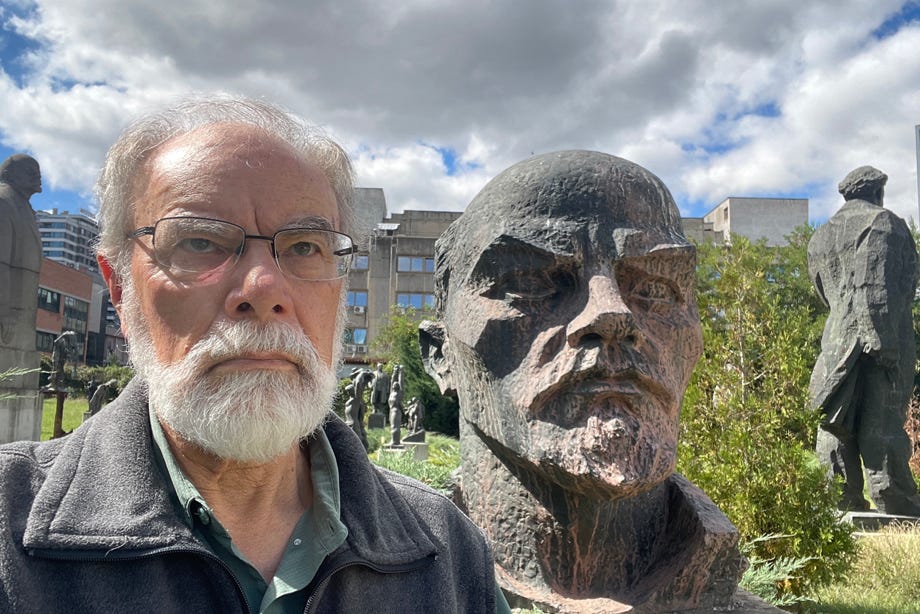

My main destination for the day was (what I consider) one of Sofia’s most interesting museums, the Museum of Socialist Art. Bulgaria is unusual among former Soviet satellite countries in that it does not deny its former Communist heritage, and this museum acknowledges this period by accommodating works of art from the socialist period. One of the departments of the National Museum of Bulgarian Art, this museum opened in 2011 in a somewhat obscure location south-east of the city centre with very little parking (making the option to walk even more attractive to me).

Google Maps helpfully suggested a walking route of 4.3 kilometres from my hotel (each way) that avoided many of the main roads, taking a route through some of Sofia’s beautiful extensive parklands and even tracks through an extensive bushland area known as Borisova Gradina Park.

However, I came upon my first example of socialist art just a couple hundred metres south-east of my hotel, this being the huge Soviet War Memorial in Knyazheska Garden. Soviet war memorials have been removed in many parts of Eastern Europe, but it remains standing in Sofia despite considerable controversy. This controversy was evident when I saw the monument this morning as there were splashes of blue and yellow paint on parts of the monument (signifying solidarity with Ukraine in its war against Russia), and the main slogan on the front of the moment reading “The Soviet Liberating Army is appreciated by the Bulgarian people” had been splashed with red paint representing blood.

Despite the understandable political vandalism, the memorial itself was a superb example of large-scale socialist realist art, with finely crafted bronze friezes on all four sides of the main memorial as well as the main sculpture atop the obelisk and additional sculptures at the beginning of the long formal pathway to the moment from the nearby main road.

With my appetite for socialist realist artworks well and truly whetted, I continued my walk to the museum past the huge Vasil Levski National Stadium, past the Bulgarian Army Stadium, through Boris Gradina Park, past the Television Tower, along Dragan Tsankov Boulevarde past the Russian Embassy and the Interpred World Trade Centre, and eventually into Lachezar Stanchev Street where the Museum is located.

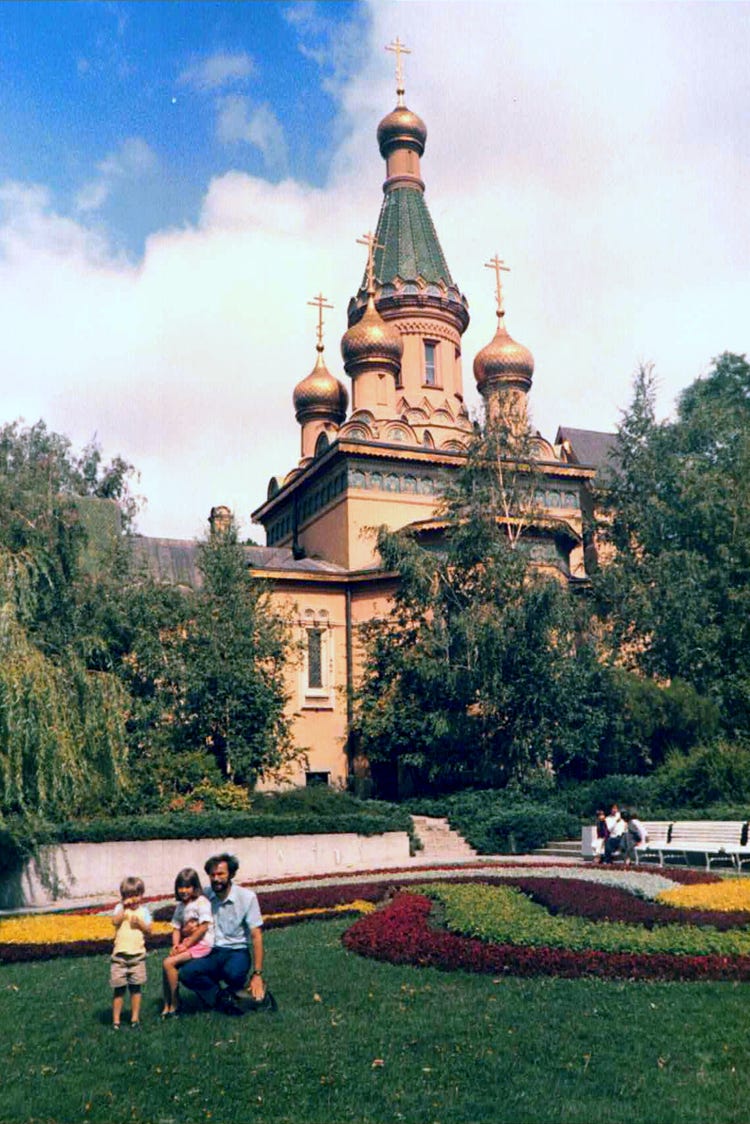

The Museum is situated around the back of the National Institute of Immovable Cultural Heritage, which means visitors need to negotiate their way into the compound past some overweight, grim looking guards at the barrier gate. I managed to do so, and as I approached the Museum, an instantly familiar sight greeted me. If you look at the right-hand 1987 photo above, you can see a red star at the top of the spire under renovation on what was then the Communist Party Headquarters Building (now the Parliament of Bulgaria). The red star has been replaced by a national flag on the building, but the star has been preserved at the entrance to the Museum.

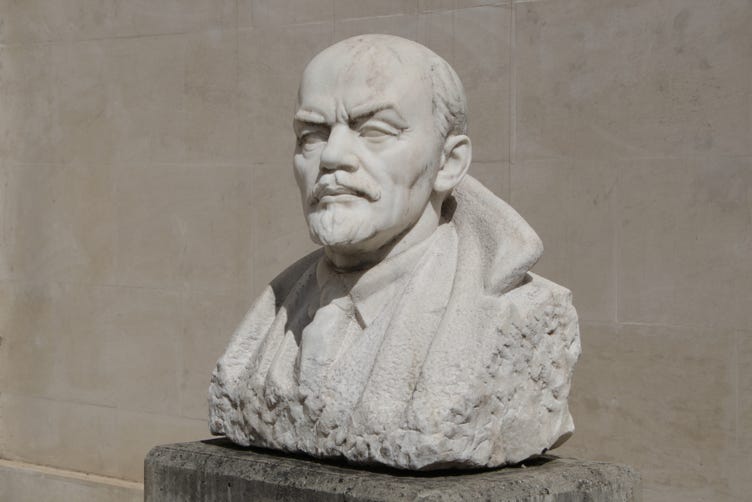

The most interesting part (by far) of the Museum was the outside park, which contained about 80 Communist-era sculptures. Amazingly, it was possible to wander around the grounds at will before buying the entry ticket, quite cheap at 3 leva ($2.30, seniors’ price), which seemed intended to provide viewing a compilation of wonderfully hyperbolic propaganda newsreels from the Communist era in a small viewing room and entry into a somewhat sterile room with some paintings that were markedly less inspirational than the outside sculptures.

I read some online reviews that claim an hour is more than enough time to visit this Museum. I stayed two and a half hours and still felt I was discovering new details right up to the time of my departure. Needless to say, I managed to get lots and lots of photos.

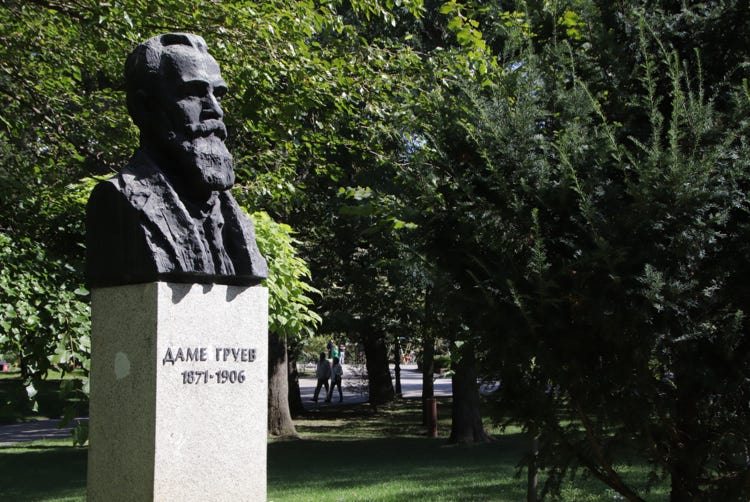

My walk back to the hotel took a slightly different route after passing through the wooded section of Borisova Gradina Park. I had a quick look at the Bulgarian Army Stadium which seems to be the centre of the CSKA (Central Sports Club of the Army) soccer team which competes in the National First League competition, and then walked through the more developed section of Borisova Gradina Park where there were well formed pathways, statues, children’s playgrounds and gardens.

The next section of my walk took me across the (undeservedly, I felt) famous Eagle Bridge. Built in 1891 and marked by four eagles (one on each corner of the bridge) symbolising freedom, the bridge was – to put it politely – quite small.

Rather than just walking on past the Soviet War Memorial that I had visited this morning, I did another circuit as the sun was shining on it from a completely different direction, showing the excellent bronze reliefs in quite different light.

I returned to my hotel at about 3:45pm, and spent some time catching up on some work. At 6:00pm (probably a little too late) I decided to do one final walk, a 3.2 kilometre return trip to one final Soviet memorial, the Mound of Brotherhood (also known as the Brotherly Mound Monument). The light was failing by the time I arrived, but the monument was still an impressive sight, centring on a 42 metre high obelisk with several sculptures and bas-reliefs in socialist realist style featuring Red Army soldiers, happy workers, peasants and partisan fighters. In one stand-alone sculpture, the friendship between a Kalashnikov-wielding Soviet solider and a Bulgarian workers is very effectively represented.

Unfortunately, this monument is not as well maintained as the Soviet War Memorial, so parts were crumbling, the paving was breaking away and there was quite a bit of graffiti. Nonetheless, there were quite a few young people there with their bicycles, and in a graffiti-covered dry pool behind the main monument a young man was singing loudly to record a music video – not what I expected to see when I walked there.

The sun was setting as I returned to my hotel, illuminating the autumn trees in the park with a lovely golden glow as the sun sank slowly towards the horizon.