Craiova to Sofia

Distance travelled = 340 kilometres driving by road and 7.48 kilometres walking (10,010 steps).

Given my weather-based ‘adventures’ on this trip, you can imagine my joy this morning to wake up and see a clear blue cloudless sky. Yes, it was only 11°C and a strong cold wind was blowing, but the clear conditions were a real tonic.

I aimed to get an early start driving because today’s travel was to include the international border crossing from Romania into Bulgaria. I did some research last night and the crossing I intended to use had received devastatingly bad reviews (1.8 out of 5 stars), largely from truck drivers who described the crossing as a disgrace because of the long lines of waiting vehicles that were said to run for about ten kilometres. Those reviews didn’t really help me to get a sound night’s sleep.

After an excellent breakfast I managed to start driving at 8:10am. Being Sunday morning the streets of Craiova were almost deserted, and after the previous day’s experience it was actually a pleasure to use the sun visor to contain the glare of the low morning sun.

The blue skies were somewhat short-lived though. As I drove south towards the border, I seemed to catch up with the thick band of grey clouds that had brought heavy overnight rain in Craiova, and so after the mid-point between Craiova and the border I found myself driving in dull, grey, overcast conditions – although no rainfall.

The border between Romania and Bulgaria is marked by the Danube River. The town on the Romanian side of the border (where the border formalities are completed) is called Calafat. Sure enough, almost ten kilometres before reaching Calafat, a continuous line of large semi-trailers came into view, parked on the road in a continuous line. Clearly, this border crossing was a very significant one for international trade.

However, it wasn’t a crossing that many cars seemed to be using. I followed the example of a handful of other cars and kept driving towards Calafat on the wrong (i.e. left) side of the road, occasionally ducking into the line of trucks to avoid hitting oncoming cars and trucks. When I arrived at the border processing point, there were just three cars in front of me (but perhaps a few thousand trucks behind me).

In stark contrast to my experience crossing from Romania into Bulgaria at Ruse in 1987, everything was done in about 10 minutes. Of course, no visa is required these days, so there was just a quick inspection (and stamping) of my passport, a check of the rental car’s papers, followed by a payment of 27 lei (about $8.20 Australian) for the bridge toll, and I found myself driving across the (fairly) new bridge over the Danube River to the Bulgarian border town of Vidin (Видин). Surprisingly, there were no entry formalities into Bulgaria – no passport stamp, no checking papers, just driving off the bridge and along the narrow highway.

There was, however, one formality I knew I had to undertake. Bulgaria uses an unusual system for its road tolls. There are no toll gates, but there are cameras, and every car entering the country needs to obtain what the Bulgarians call a vinetka (винетка), which is translated as “vignette” to avoid hefty fines. Vignettes are not advertised, and I only knew about them from my research before leaving Australia, plus a reminder from the rental company when I collected the car in Bucharest. I stopped at the first open petrol station (about 20 kilometres beyond Vidin), withdrew some cash from an ATM, and purchased my vignette. Everything seems to be done electronically – there is nothing to display in the car, but the car’s licence plate and details were recorded, presumably to match with the OCR of the tell-tale cameras that can be seen above many of the highways. The vignette wasn’t expensive; 20 leva ($15) for seven days or 30 leva ($23) for a month – I needed nine days, so the one month vignette was the best value.

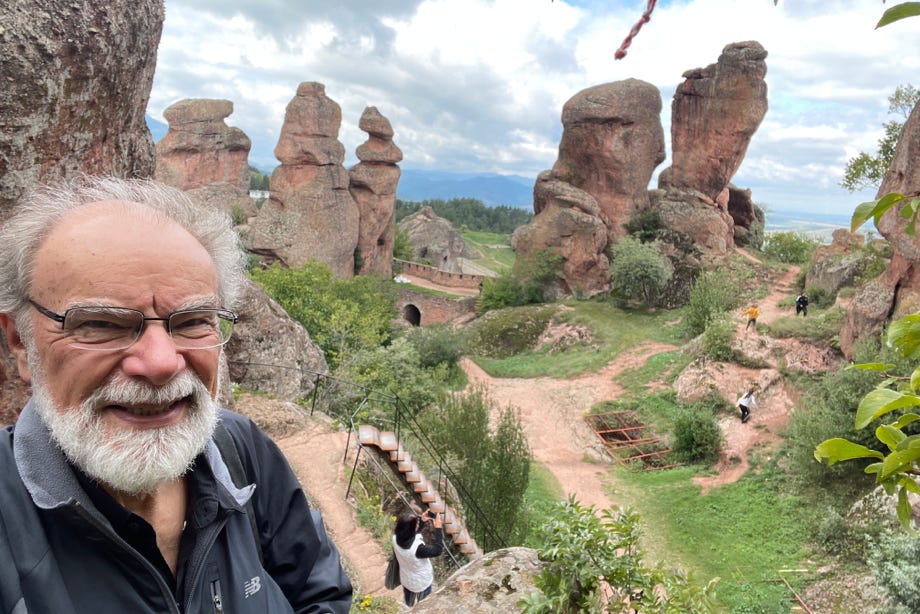

My first planned stop for the day was at the somewhat remote small mountain town of Belogradchik (Белоградчик). The town and its surrounding area of about 50 square kilometres are marked by unusual pillar-like formations in the pink-orange sandstones and conglomerates that comprise the region’s geology.

It is difficult to get a good vantage point to show the relationship between the town and the rocks that tower above it, but after a bit of circling around the town I headed to Kaleto Fortress, which overlooks the town from its southern fringe. Built into the rock pillars and making great defensive use of their weird shapes, the fortress was originally established by the Romans, and subsequently expanded by successive invaders – the Byzantines, the Turks, and yes, even the Bulgarians.

Visiting the fortress required quite a bit of ascending steep flights of steps and scrambling over rough, rocky outcrops, a not always pleasant experience as the temperature had dropped to 7°C and a very strong wind was blowing. Unfortunately, photography was challenging in the dark, overcast conditions because the rocks seemed to absorb light in a similar way that blotting paper absorbs water.

And then – a distant sight provided hope! As I looked to the west, I could see a few small patches of sunlight opening up in the distance. Because the winds were so strong, the patches of sunlight were appearing, disappearing and morphing at high speed, but in general they were moving in the ‘right’ direction, i.e. towards Belogradchik. I decided to stay waiting in the cold wind in the hope of some good light.

It eventually arrived, but it lasted less than two minutes. Every photo of Belogradchik you can see here with sunlight was taken during those brief two minutes, after which the sun was quickly obscured once again by the thick clouds and I took my leave.

I continued my drive south, passing through alternate bands of sunlight and thick clouds as I did so. I made one brief unplanned stop just north of the village of Barzia (Бързия) where I came across a large socialist-era monument of the type that was commonplace during my drive through Bulgaria in 1987. This seemed to be a large example of a mass-produced standard statue from the Communist era based on Ivan Neshev’s 1969 sculpture titled “First Day”, the original of which is now in the Museum of Socialist Art in Sofia. Today’s monument near Barzia was the only one I saw on today’s drive, a bit disappointing but hopefully there will be many more to see during my travels in the coming week.

I reached the outskirts of Bulgaria’s capital, Sofia (София), at about 3:30pm. I made a quick stop for fuel (only being told half-way through the tank filling that payment would have to be in cash, no cards accepted), and headed for my accommodation, the Intercontinental Hotel on Narodno Sabranie Place in central Sofia. I chose this hotel because it was within walking distance of the city centre and because I could pay for my accommodation using points.

One of the best decisions I made with my car rental was including GPS navigation. I vividly recall the challenges and the stresses of driving through Eastern European cities in 1987 with the (very) poor quality paper maps available. Navigating was not only a challenge within the cities, but in rural areas as well where (according to my informal analysis) the main intention of road signs seemed to be to confuse potential invaders rather than to guide foreign drivers. By contrast, navigating both the cities and the countryside has been a dream on this trip with clear electronic maps and verbal directions (with a well-spoken Australian accent!).

With supreme confidence arising from my hitherto positive experiences of navigation, I headed for my hotel. What I didn’t know – but I soon discovered – was that Narodno Sabranie Place (the location of my hotel) was entirely closed for re-paving. After driving in smaller and smaller concentric circles, I found an illegal parking spot in a small street behind the hotel, walked the short distance to the hotel and checked in. “No problem” said the young man in the reception area, “just give me the key and I will go and move the car and park it for you”. I have no idea where the car has been parked, but I’ve been assured it is both safe and legal (in the US, they call this valet parking).

Having checked in, I couldn’t help noticing that the sun had re-emerged and the skies were clear, so I decided to make the most of the good light and explore the city centre near the hotel. My recollection of Sofia from my brief 1987 visit was that it was a lovely elegant city, and this afternoon’s walk reinforced that impression. A short walk to the west of the hotel brought me to Prince Aleksandyr I Square, surrounded by an array of beautiful buildings including the Palace National Art Gallery, the Bulgarian Archaeological Museum and the National Assembly Building, and just a little further to the west, the Parliament Building and the Council of Ministers Buildings.

The last time I visited Prince Aleksandyr I Square (in 1987) it was known as September 9th Square, commemorating the coup in 1944 that brought Communism to Bulgaria. At that time, the central feature of the square was the mausoleum housing the embalmed body of Bulgaria’s first Communist President, Georgi Dimitrov. I took a photo of the square on my 1987 visit, and I managed to get a comparative view this afternoon; you can see the comparative photos to the right (with the 1987 view shown in the red frame).

The sunlight lasted for about an hour, during which I tried to get some photos of key buildings to give an initial impression of this lovely city. As the light faded, a rock band started playing some music almost precisely where Dimitrov’s mausoleum once stood, emphasising that despite its enduring elegance, Sofia today has a very different atmosphere than it did in 1987. You can see my one-and-a-half minute video of the Square with music playing HERE.