The sky was still completely black when I woke to my alarm this morning at 5:45am. Even though Sunday is a normal working day in Oman, the first day of the working week, I needed to get an early start to fit in with another set of quirky opening hours. My first (and main) destination for the day was “The Lost City of Wubar”, which is situated within the tiny settlement of Ubar. Situated 170 kilometres north of Salalah, this UNESCO World Heritage site opens from 9:00am to midday, when it closes until 3:00pm, remaining open until 6:00pm.

I managed to get to breakfast when the hotel restaurant opened at 6:30am, just as colour was starting to appear in the eastern sky, and I was on my way to Ubar. Even with a diversion to buy petrol, I arrived in Ubar just two hours later at 9:30am, the roads being consistently excellent all the way.

Ubar is a tiny town, and the excavations of ancient Wubar occupy only a tiny proportion of that tiny settlement. Indeed, even though I did three circuits of the “city” and a couple of diagonal passes, the total distance I walked while there was only a kilometre.

Wubar was re-discovered, or “found” in 1990 using satellites, making its identity as a “Lost City” somewhat of a misnomer. Having said that, there is so little to see there that perhaps there is an entire city still waiting to be found there.

Having said that, the Arab traders and residents at the time did not live in traditional dwellings, but in tents with sides that could be opened to allow cooling breezes. Therefore, we wouldn’t expect many remains of most of the “city” to survive except for fire pits, of which there are many, together with a permanent fortress that was also the home of the king.

Poetically referred to by some people as “Atlantis of the Sands” and also known by the names “Shisr” and “Iram”, Wubar seems to have come into existence some time before 2800BC. The city was originally a processing and shipping centre for frankincense, and was located at the intersection of busy trading routes.

The Qu’ran specifically mentions Wubar (by its alternative name of Iram), saying that the city was destroyed by God because of the debauchery of its residents. To quote the Qu’ran 89:6–14: “Did you not see how your Lord dealt with ’Ȃd, ˹the people˺ of Iram, with ˹their˺ great stature, unmatched in any other land? And Thamûd, who carved ˹their homes into˺ the rocks in the ˹Stone˺ Valley and the Pharaoh of mighty structures? They all transgressed throughout the land, spreading much corruption there, so your Lord unleashed on them a scourge of punishment. ˹For˺ your Lord is truly vigilant.”

On the other hand, more recent geographical evidence suggests that Wubar was destroyed when an earthquake caused a large limestone slab beneath the city to collapse some time between 300 and 500AD, causing a sinkhole into which the city fell.

After completing some circuits of the remains of the city, I ventured down into the sandy base of the sinkhole to find a recently constructed flight of steps giving access to an underground cavern. As I peered down the steps, the sun cast a perfectly centred, quite eerie shadow of my profile on the floor below.

Feeling somewhat like a phoney imitation of Indiana Jones, I gingerly descended the steep steps hoping to find more historic remains of ancient Wubar. What I found instead was a cubic concrete chamber, empty apart from what seemed to be hundreds of wasps’ nests on the ceiling, leading through a further unprotected opening into an unlit, seemingly bottomless pit with what seemed to be a random array of disused water pipes.

After 50 minutes, I felt I had seen everything several times over, so I began my return drive back to Salalah at 10:20am. I made one stop on the return trip at another (again small) UNESCO World Heritage site, Wadi Dawkar, about 40 kilometres north of Salalah and only one kilometre west of the main highway linking Salalah with Muscat.

With an area of about five square kilometres, Wadi Dawkar is a natural area for the growth of frankincense. This natural suitability has been harnessed by the development of an irrigated and carefully tended plantation of frankincense trees numbering about five thousand. I don’t think anyone would grow frankincense trees for their beauty, but they are the source of high-value resin that is widely used for incense burning throughout the Middle East. I had seen it for sale in many of the souqs and markets I had visited in Oman, but Salalah is really the ‘world capital’ of frankincense as it is the largest among the very few places it grows (the other locations being even more remote than here).

When I arrived, I was greeted enthusiastically by the one gardener who was tending the plants. He introduced himself as coming from Pakistan, adding that he was a Christian – a Catholic one. He was obviously very proud of the trees and insisted on showing me the best one in the garden, followed by some that were just outside the UNESCO preservation garden in the “wild wadi”, including some self-sown trees that were several hundred years old.

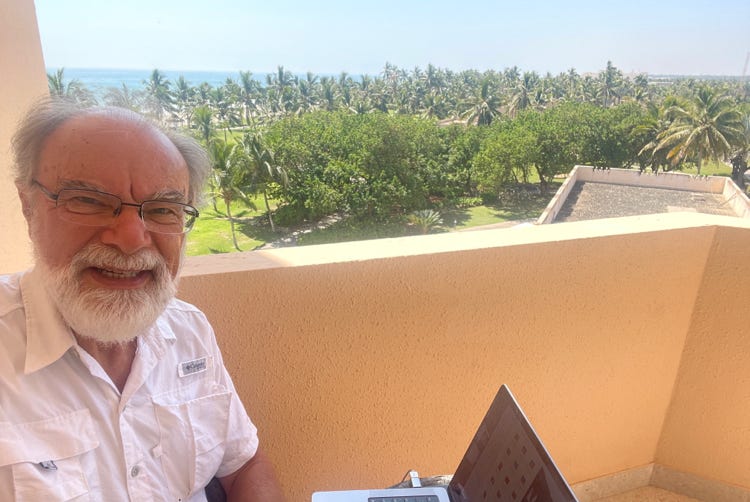

I returned to my hotel at 12:30pm, five hours after setting out this morning. I needed to catch up on several hours of work this afternoon, so the early return was a real blessing, albeit a planned one. I spend most of the rest of the afternoon working, first on the small balcony of the room at my hotel, and when the sun moved around and started ‘cooking’ the balcony, in my room. Given the lovely views from my hotel room, I couldn’t help thinking that there are many worse places to catch up on work than the southern coastline of Oman on a sunny Sunday afternoon.