Europe 1987

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan 2018

We enjoyed a lovely breakfast of fresh rolls, coffee, meat, cheese and jam. We left Nuremberg at about 9:45am to embark on the beginning of the more adventurous part of the trip – penetrating the Iron Curtain into Communist Eastern Europe. I had visited Czechoslovakia (without the rest of the family) three years previously in 1984, and I was under no illusions that travel on the other side of the border would be as straightforward as it had been for us so far.

I filled the car with petrol for the coming journey, and then drove around the city centre of Nuremberg for a few last photos before starting the drive east towards Czechoslovakia – or to refer to it by its official name, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (CSSR). Before leaving West Germany, we stopped at Amberg to post some letters and Vohenstrauss for lunch and to have a look around the old city, including the beautiful old Town Hall building and church.

The last West German town we drove through before the border crossing was Waidhaus, about two kilometres from the frontier. As we drove through Waidhaus, I remember thinking that if there was a Soviet invasion of Western Europe, the residents of this town would almost certainly know about it before anyone else in the world as they watched the Soviet tanks rolling through the streets. It also reminded me of the comment made by a colleague at Stonyhurst shortly before I had left to embark on this trip. He was a Physics teacher who had taught for a few years in Leningrad in the early 1960s. His words to me were these: “You know, I used to lie in bed at night and worry about swarms of Soviet tanks rolling westwards across the fields and through the towns of Western Europe, but then I bought a Lada, so now I know there is no chance that they could ever get as far as the English Channel”.

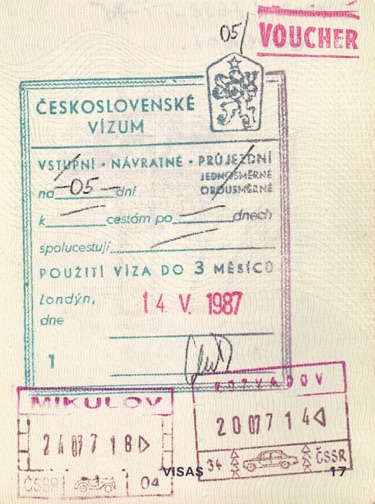

About two kilometres east of Waidhaus, our first crossing of an East-West border at Rozvadov to enter Czechoslovakia went surprisingly well. Although Liesl was pretty terrified by all the gun-carrying border guards, the formalities only took about 20 minutes, and there was only a cursory inspection of the luggage in the car boot.

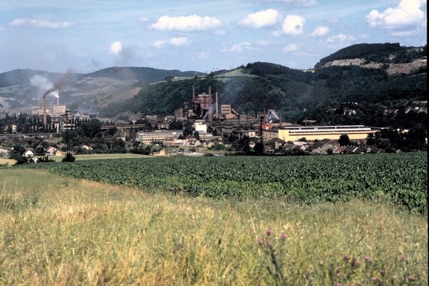

As soon as we crossed the border, it was immediately evident that the scenery was quite different from West Germany, with flatter land and towns with older, more run-down appearances. We made three short photo stops to record our initial impressions of the differences behind the Iron Curtain in Stříbro, Pilsen (on the 605 highway coming into the city from the west) and Beroun.

We arrived in Prague mid-afternoon, and our first stop had to be Pragotours, the local subsidiary of Čedok, the government monopoly that controls all travel in Czechoslovakia. Because the Youth Hostels Association (YHA) has no presence in Czechoslovakia, I had arranged for us to stay with a family (any family; we couldn’t choose) in a private (but obviously government-approved) home. However, as was the normal practice, I hadn’t been notified of the name or address of “our” flat, so I needed to visit the Pragotours office to find out which home had been allocated to us and where it was located.

This process took about an hour and a quarter, during which time Di waited with the three children in the (increasingly hot) car. Eventually I learned that we were to stay in a flat owned by a Mr Blaha, so I returned to the car and navigated our way to the street where his flat was located, Podskalská 22, Nové Město (New Town).

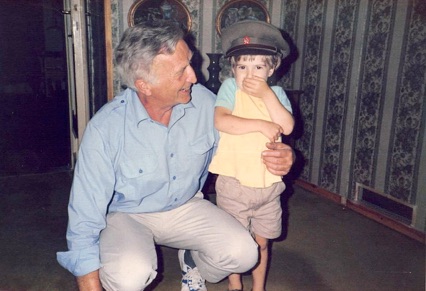

The outside appearance of the building was uninviting to say the least, being very run down indeed. However, the inside of the flat was nicely set up and Mr Blaha was a delightful and welcoming host. Although we had expected to be sharing the flat with Mr Blaha during our stay, we only shared for the first night as he went to stay at his grandchildren’s place early the following morning.

Having said that, we did get a shock that evening when there was a loud knock at the door. When Mr Blaha opened the door a young uniformed soldier entered the flat. As things turned out, the soldier was Mr Blaha’s son, who was doing his one year of compulsory military service. Mr Blaha explained that normal National Service is two years, but he didn’t have enough money to pay to get his son out of it entirely, although he did have enough to get it reduced from two years to one year.

We then spent much of the evening chatting with Mr Blaha about what he described as the tragedies of Czechoslovakia: “First there was the tragedy of Hitler, then there was the tragedy of Stalin, then there was the tragedy of the Prague Spring in 1968 and the Soviet invasion. We are still living in a tragedy…”. As we continued in our conversation, I thought to myself “this is the guy the government has approved for us to stay with – what do those who don’t get approval think?”.

Day 8

Nuremberg to Prague

Monday 20 July 1987