China 1982

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan 2018

Shanghai is one of those place names (like Peking) that stirs the emotions. A large treaty port on the China coastline, it was famous in the 1930s for its racy and decadent lifestyle. For a person to be “shanghaied” is even a common turn of phrase, meaning to be kidnapped or tricked into working for you, traditionally by being drugged and taken away by ship. That’s the Shanghai of my imagination!

All that changed when the Japanese invaded and occupied the city in November 1937. It became positively puritanical after the Communists seized the city in the late stages of the civil war, and these days, Shanghai is regarded as a mere shadow of its former glorious self. Once more vibrant and influential than Hong Kong, no-one seriously compares the two cities today, and the line of grand European buildings that line the Shanghai riverfront are vague reminders of what was once one of the world’s greatest cities.

My one single day today in Shanghai was something of a disappointment, not because the city failed to excite, but because we had to try and squeeze the study of 11 million people into a single day. Moreover, because of a mix-up in travel arrangements we had to miss our scheduled boat trip on the Huangpu River, this being replaced by a visit to a classical garden (the Yu Yuan), an arts and crafts institute (which was really a TT), and a trade exhibition (read friendship store).

Having said that, I did see something of Shanghai through the bus window and on two walks, and what I saw was certainly interesting. I woke up to the sound of music coming in through the hotel window. Looking outside with a good view down to the Bund, I saw the riverside area filled with local people doing their tai chi exercises. The Bund is something of an infamous zone as this was the wharf area that during the days of European power had signs proclaiming “Dogs and Chinese Not Allowed”.

The Peace Hotel where we are staying is one of Shanghai’s great institutions. Originally known as the Cathay Hotel, it was built between 1926 and 1929 by Victor Sassoon, a wealthy British-Iraqi-Jewish entrepreneur with extensive business interests across Bombay, Hong Kong Kong and Shanghai. With ten storeys, the hotel was one of the first high-rise buildings in what was then known as the Far East, and for many years it was the highest building in Shanghai. Noel Coward stayed there in 1930 and wrote “Private Lives” during his stay.

When the Communists took over Shanghai in 1949, the hotel was turned into government offices. However, it re-opened as a hotel in 1956 with a new name, the Peace Hotel. During the Cultural Revolution in 1967, the hotel was used by the hard-line “Gang of Four”, the so-called Shanghai Radicals, as the headquarters of the Shanghai Commune. Now it is a hotel once again, and from a practical point of view, offers a wonderful experience overlooking the sights and sounds of the bustling shipping movements of the Huangpu River from its upper floors. If only the air hadn’t been so hazy I might have been able to get a good view of the low factories and the vegetable on the east bank of the river.

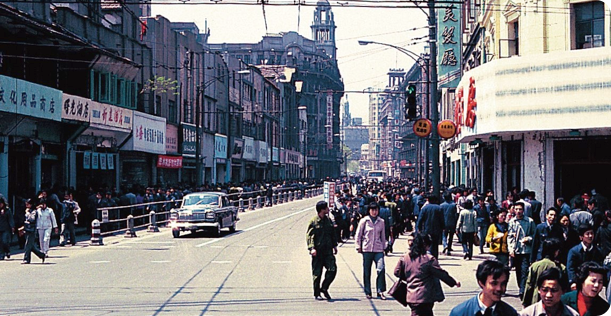

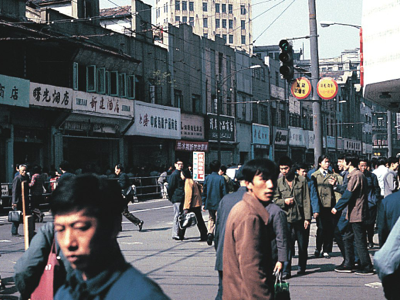

Nanking Road is obviously Shanghai’s central artery. Twisting its way from the east to the west away from the Huangpu River, it is lined by two and three storey high buildings that mostly house shops on the ground level with residences on the upper level(s). There are so many people walking along Nanking Road that the footpaths have been widened with the erection of metal bars on the roadway, leaving just a narrow thoroughfare for the admittedly minute number of cars on this, Shanghai’s busiest roadway.

It was fascinating to see the traffic lights in Nanking Road, and in Shanghai in general, where the green light was on top and the red light was at the bottom. This dates back to the Cultural Revolution when the hard-line officials said it was no longer appropriate that red should mean ‘stop’. Being the colour of communism, they decreed that red should mean ‘go’. Consequently the order of the vertical traffic lights were reversed – some sets of traffic lights are horizontal and I don’t know whether these were changed or not. The meaning of the lights has now reverted to international standards where red means stop, but the re-ordered lights remain. I can imagine that if drivers in Shanghai actually took any notice of traffic lights, this would all have caused, and would still be causing, some dangerous confusion.

For a flat city, Shanghai’s roads have a remarkable number of twists and turns. The European architecture contrasts strongly with every other city we visited in China (with the possible exception of the old part of Wuhan), although the old colonial mansions were often hard to see behind the high walls that lined most of the roads we drove along.

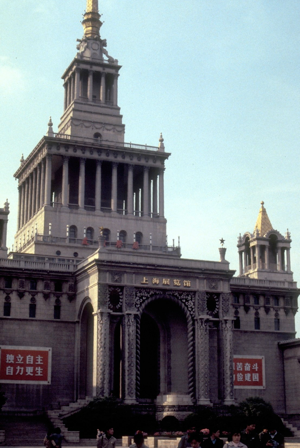

In the afternoon we visited the Shanghai Industrial Exhibition Hall. The interior exhibition was a mildly interesting array of goods manufactured in Shanghai, such as television sets and washing machines (most of which were inexplicably loosely wrapped in clear plastic), but I thought the real interest lay in the building itself. Built in 1955 in full Stalinist architectural style as a gift from the USSR, it was originally known as the Chinese-Soviet Friendship Building. Subsequent shifts in geopolitics explain the change of name to the Shanghai Industrial Exhibition Hall.

The people of Shanghai are more adventurous in their fashion that other cities in China, and more in a hurry – there is more hustle and bustle and the feel of a Western city (but an old Western city) than any of the other cities in China we have visited. There was even advertising here, much of it being for industrial machinery and equipment, but some of it for consumer goods such as soap and television sets.

A few passing observations from Shanghai:

• Chinese children under the age of five or so have an intriguing split through the crotch of their clothes to enable them to squat and attend to any pressing needs without the need for undressing and re-dressing.

• The price of petrol in China is 65 fen (0.65 yuan) per litre.

• The price of bicycles starts at 108 yuan.

• Bus fares are a uniform 5 fen per trip.

• People who commit murder in China are shot as a punishment under the slogan “blood for blood”, with the sentence usually being carried out on the same day that the sentence has been handed down on the basis that a long delay would be cruel.

• Workers’ palaces, children’s palaces and youth palaces provide extra-curricular activities that replace the brothels and opium dens of the old society.

After our all-too-brief time in Shanghai, we embarked on a late afternoon drive back to Shanghai’s Hongqiao Airport, out to the west beyond the urban margin of Shanghai. The drive took us through the area we had driven through in the darkness of the previous night, so it was good to see something of Shanghai’s residential areas that had previously been invisible to us. The residential areas were interspersed by what seemed to be a dense network of canals, and the large numbers of boats on the canals suggested that they formed an important transport network. It was immediately obvious that we were crossing a significant number of canals as our bus bumped its way over humped bridges that had been built, I guess, to provide space beneath them for boats to pass.

I thought a very telling comment was offered by one of my fellow travellers as we approached the airport: “Isn’t it extraordinary to be in a city of over ten million people and not see a single tall building”. Shanghai has a high population density, but unlike many of the world’s cities – and even Peking in China –that density has not resulted in any vertical expansion whatsoever.

I’m getting a bit braver now that my trip is almost over. I haven’t dared to take photos at other Chinese airports, but I did manage discreetly to get some photos of Shanghai’s Hongqiao Airport. With the exception of Peking, Shanghai’s Airport was a bit busier than other airports we have passed through with more planes visible on the tarmac, although they are very quiet compared with airports in the West. As a plane enthusiast, it was a joy to see modern British Tridents sharing the tarmac with elegant Soviet Ilyushin Il-18s and Antonov An-24s, although I wish I could have also photographed some of the many Antonov An-2 biplanes that I saw in Sian.

Our flight to Canton was on another CAAC Trident, this one registered B-260. Arriving after dark, we once again had the experience of driving from the airport to our hotel (the Pai Yun Hotel) without seeing anything.

Day 21

Shanghai, China

Thursday

22 April 1982