China 1982

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan 2018

Our entire morning today was spent at the Da Ming Gong (or Great Bright Palace) People’s Commune, about 15 kilometres to the north-east of Sian city (in the far outer suburbs near the remains of foundations of some Tang Dynasty royal buildings). I was thrilled to visit a commune at last; more than 80% of China’s population are farmers (officially referred to as “peasants”), so having the first-hand opportunity to visit a farm (or farming complex, which is what a commune really is) was very much appreciated.

It was a great visit, the evidence of which is a roll of photos and nine pages of notes. Since the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s and early 1960s, communes have been the basic unit of organisation of China’s agricultural system. Roughly corresponding to the pre-revolutionary “district”, each commune is divided into production brigades (roughly the historical “village”, each of which is divided into production teams (roughly the historical “extended family”). Everything in the commune is shared, and even kitchens and dining facilities are communal. Apart from the farmers’ own needs, everything produced is sold to the government.

Our visit began by being taken to the commune office where we received a briefing from the Commune Director, Mr Wang. He began by saying that the population of the commune is about 23,000 people comprising 5,000 households. The commune is divided into 23 production brigades and 81 production teams. The area under cultivation is 1,753 hectares, the main crops being wheat, cotton and vegetables.

The commune also operates factories, including farm implement repairs, hardware processing, chemical engineering, artificial leather manufacture, woollen textiles, leather shoes and handicrafts manufacture (such as tricolour porcelain horses). The commune also operates 55 large trucks and 180 tractors.

We were told that before the Revolution in 1949, 95% of China’s cultivated land was owned by landlords (landlords comprising 5% of the national population at the time), and this led to low production levels and widespread poor standards of living. The area of Sian was liberated with the arrival of Communist forces in 1949, and in 1951 widespread land reform was implemented as land was taken from the landlords and redistributed to the peasants who were farming the land.

In 1953, the farmers were organised into mutual aid production groups, and in 1958 the people’s commune was established. We were told that since the establishment of the commune, the peasants have been farming their own land and they have enthusiastically expanded the area under irrigation to the extent that the entire commune can now be irrigated. Consequently, in 1981 the wheat yield reached a peak of 4,500 kilograms per hectare.

Last autumn the commune experienced a poor harvest as a result of a series of national disasters (too much rain). There is a primary requirement to fulfil the state quota, so in order to fill that requirement, there was a shift in 1981 towards more sideline production. Consequently, the commune’s total output hit record levels, and the state quota was over-filled by 3 million yuan. In 1981, the quantities sold to the state were 2.45 million kilograms of grain, 40 million kilograms of vegetables, 110,000 kilograms of ginned cotton, 7,000 fat pigs, 110,000 kilograms of fresh eggs, 300,000 kilograms of fresh fruit, and over a million kilograms of fresh milk. According to the regulations, 40% of grain production, 90% of cotton, and 90% of the vegetables grown should be sold to the state in return for income, and 5% of the income thus earned is then paid to the state as tax.

The annual grain ration for members of the commune is at least 250 kilograms per person. The average cash income per person for the year in 1981 was 205 yuan, up from 180 yuan per person in 1980. During 1981, the farmers built many new houses with a total of 50,000 square metres floor area. Despite the poor harvest in 1981, the farmers bought many new electrical goods, including 2,500 television sets and 2,800 sewing machines.

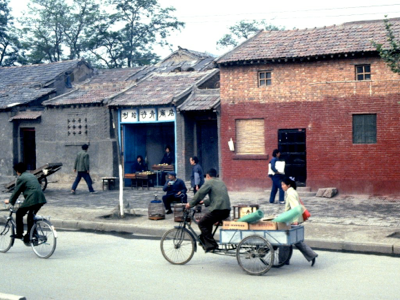

Bicycles are the main means of transport, and there are 7,000 bicycles for the commune’s 5,000 households.

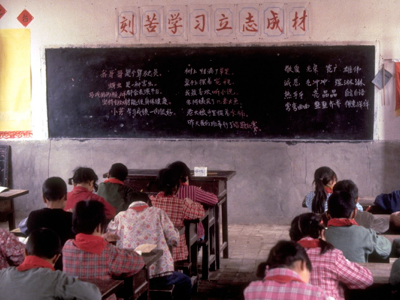

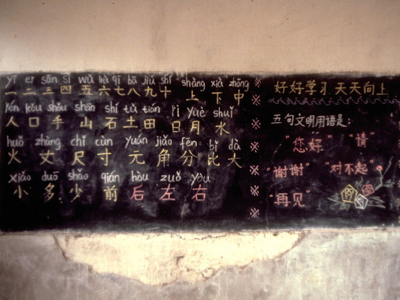

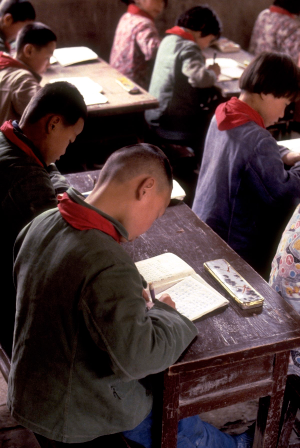

The commune has four middle schools and six primary schools with a combined enrolment of 5,300 students. This commune has achieved universal middle school education. School fees are 4 to 5 yuan per student per half-year, which helps pay the teachers’ salaries of 50 yuan per month. The school day lasts from 8:00 to 12:00 noon and 2:00pm to 5:00pm, with most students going home for lunch during the two-hour break. Teachers are appointed by the municipal authority. Although in theory teachers can move to other schools within the city and even to other areas of China, the choice to do so is usually the government’s to make.

The commune also runs a hospital that is supported by separate clinics in each brigade. The hospital includes a surgeon, a paediatrics unit, several gynaecological departments that employ in total 30 doctors, 70 barefoot doctors (paramedics who travel around the bridades), and some nurses. The commune charges an annual fee for medical care of 1 yuan per working farmer, after which all medical care is provided free of charge.

Buying and selling is done through a commune-run co-operative store that has six sub-branches across the commune. The stores are responsible for providing the day-to-day needs of commune members as well as selling the commune’s side-products. The commune has a projection (of films) team of three projectionists. Every night they travel across the commune to visit teams and brigades to show films, often in the open-air.

We were told that compared with “the past”, the commune has produced “great achievements”, although compared with neighbouring communes, a lot of work is still needed to catch up. “So we are striving to study the Party’s rural policy and learn from advanced communes in other areas to raise living standards”.

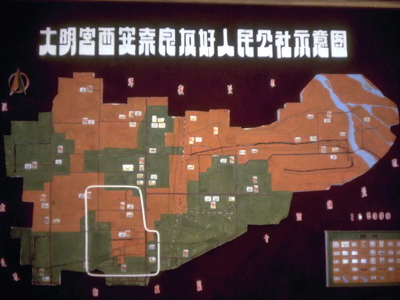

We were shown a wall map of the commune that apparently measured about 10 kilometres wide (east-west) by 5 kilometres north-south. Green areas represented areas of vegetable cultivation, while brown areas represented areas of grain cultivation. The white circle indicated the area containing the ruins of the Tang Dynasty palace after which the commune is named.

Following the briefing, we saw the commune’s kindergarten, salesroom for honoured foreign guests, a primary school, clinic, a peasant’s house and the farming fields before returning to Mr Wang’s office.

Our hostess in the courthouse house I visited was Mrs Chou, who explained through a translator that 11 people lived in the compound, which comprised a courtyard, laundry, kitchen and two small rooms, each measuring 6 metres by 4 metres. The house was just over 30 years old, and therefore a remnant of “the old society”.

The 11 people were herself, five children, two daughters-in-law, one grandchild and one mother-in-law (plus someone else who remained unidentified), making up four generations in total. Her husband, eldest son and daughter-in-law all work in Sian, so don’t live in the house. Mrs Chou’s days are spent looking after the house and her grandchildren, while the other adult residents of the house work in the commune’s farming fields.

The entire family’s annual income in 1981 was 1,100 yuan. They grew their own food, and both water and electricity were provided free of charge by the commune. After expenses, the family was able to save 600 yuan last year (1981). Her husband and eldest son who work in Sian receive 130 yuan per month, but they hand over all of their salaries to the commune.

Before 1949 (or as it was described, “before Liberation”, there was only one bicycle in the village where Mrs Chou lived, but now each family had a bicycle. In Mrs Chou’s household, there were six bicycles, seven wristwatches, one television set, and two sewing machines.

Although the land is owned communally, houses are privately owned. When a family wants to build a new house, they apply to the commune authorities for a plot of land. Commune workers retire at the age of 65 for the men and 60 for the women. Retirees who have their own children and have no financial problems are supported by their children after retiring. Those who have financial difficulties (which is not many) receive a subsidy from the government. About 12 people in Mrs Chou’s village have no children, so they are supported collectively by the production team and brigade. Overall, there are 2,000 children aged below 7 years old, and 10,000 under the age of 16.

A new organisational system, known as the Responsibility System, is currently being introduced in all the production teams and brigades of the commune. The introduction began in the second half of 1980, and by the second half of 1981, every town was using the new system. Under the Responsibility System, different families assume responsibility for the production in different parts of the commune, rather than being one, large, amorphous organisational unit. So far, 80% of production teams are implementing the new system as groups of households, and 20% are implementing it as individual families.

As a result of the introduction of the Responsibility System, production has risen despite the poor seasonal weather. In 1980, the commune’s total income was 12.5 million yuan, but this rose to 15.5 million yuan in 1981. Future plans specify that yield per hectare will increase as a result of adopting the results of scientific research and increasing mechanisation. 60% of the income earned from sales to the state go to farmers as wages or salaries, and the remaining 40% is used as public money to buy machines in order to raise productivity. Every production brigade has a transportation team that take the goods produced into Sian city. For sideline production, a transport control station take the goods into the city by tractor.

The commune appeared to be slightly better than average farming areas we have seen in passing, although it seemed a long way short of being a model commune. We were allowed to wander freely, and to her mother’s obvious embarrassment, one little three-year old girl tugged some members of the group inside to see her house. It was no different to the houses that the rest of us had been invited to see more officially. In other words, it did not seem that the houses for inspection had been chosen specially.

Our afternoon seemed to be “fill in” time in Sian. We began with a visit to West Gate Tower on the old city wall. Sian four entrances into the city through the city walls, one at each of the cardinal points of the compass. The West Gate Tower is the best preserved of the four, although the courtyard of the tower is now occupied by Sian Fire Station. Frankly, the views were unexciting and fairly mundane, although they provided a good perspective on the large size of the city wall.

We then visited the only mosque in China that is built in Chinese architectural style rather than the more common Arabic style. Built in the AD700s (742AD to be specific), it is still used as an active mosque as there is a large population of about 60,000 Hui nationality people in Sian. Hui people are Han Chinese who are Moslem; all Huis are Moslem except those who join the Communist party, as they must renounce their religion as a condition of membership. Interestingly, only men worship at the mosque; Moslem women do so in their homes.

We then walked to the Drum Tower, built two years after the Bell Tower that we had visited earlier in our stay. This was a very worthwhile stop as it provided excellent views over the courtyards of the traditional homes surrounding it.

After a quick dinner at the May 1st Restaurant, we drove to the airport and had a two hour evening flight to Shanghai – another flight in a CAAC Trident three-engined jet (with the registration B-254). It was dark as we drove along the narrow roadways from Shanghai’s Hongqiao Airport to our hotel, the Peace Hotel which is located in the former European area along the Huangpu River known as “the Bund”.

As we entered the hotel’s colonial-style foyer, we were greeted with what we have been told is Shanghai’s first, and so far only, neon-lit sign – a red and white bilingual message in Chinese and English proclaiming “We have friends all over the world”. The neon sign told us clearly that we had arrived in China’s largest city – a metropolis of 11 million people – and it was not going to be like any other city in China we had visited.

Day 20

Sian, China

Wednesday

21 April 1982