China 1985

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan 2018

We spent this morning at Zhu Huizhu’s school, the Shanghai Foreign Languages Institute. After a briefing about the school from its deputy, we saw a succession of outstanding performances by the very talented students of the school, including one girl who recited three long extracts from Jane Eyre in faultless, almost BBC accented English from memory. We then toured the school, seeing lessons in progress (and noting how warmly Chinese students have to dress in their unheated classrooms) and discussing the personal “nightmare” experiences of the Cultural Revolution with the school authorities. The visit finished with informal discussions between the students of the two schools.

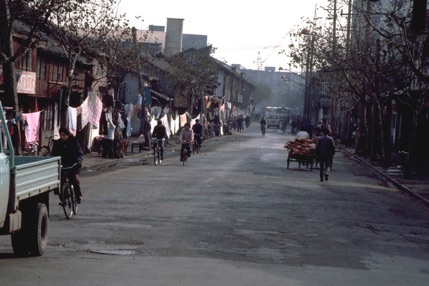

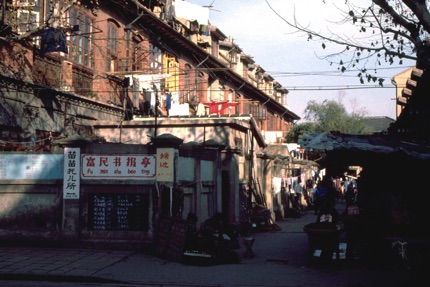

We returned to the hotel through some of the older parts of Shanghai, and after lunch we had an hour and a half free time. While most of the boys rested, armed with my new camera batteries, I went for a photographic walk along some of the narrow lanes and alleys near the hotel in the old French concession. The French architecture was obvious by the gables and skylights on the old houses, and the communal water pumps and toilets for the residents gave an almost village atmosphere to this part of the huge city. An old lady spinning yarn on an antiquated apparatus on the footpath, and the washing hanging up to dry across the footpaths added atmosphere if not ease of movement to the walk.

Later in the afternoon we travelled to the Old Chinese City, that section where the foreign powers never established control. We began by visiting the Yu Gardens, a small but exquisitely landscaped Chinese garden developed by some rich Ming Dynasty officials between 1559 and 1577. People who have seen the willow pattern plate can imagine the Yu Gardens, as they provided the basis for the plate. After the Yu Gardens, we were given half an hour to stroll around the alleyways of the old city, which presumably are safer for foreigners nowadays than they were said to be earlier this century when foreigners who entered may never have been seen again. The buildings are obviously old and appear to Westerners to be in miniature or small scale – they are two storeys in height but only 15 feet tall – the doors are perhaps 5 feet high, etc.

Most of the group then proceeded to visit the Shanghai Industrial Exhibition Hall, a Stalinist style building originally constructed by the Soviets during the 1950s and called at that time the Palace of Eternal Sino-Soviet Friendship. From there they went to the Park Hotel to partake of their one western meal for the trip. However, one of the students and I had been invited to visit the home of a Shanghai resident, so we left the group at the Industrial Exhibition Hall to meet our host at the hotel.

The invitation came from a gentleman (Ding Zhaoqing) whose brother (Ding Zhaozhang) now teaches computing at the University of New South Wales. Because Ding Zhaozhang used to live near Zhu Huizhu in Shanghai, and they had maintained contact, Zhu Huizhu had told Ding Zhaozhang of our impending trip (and he rang me a few times in Sydney with advice concerning it) and also told his brother Ding Zhaoqing that we were coming to Shanghai. Ding Zhaoqing came to our hotel with Zhu Huizhu and his niece (Ding Hailong) to invite the three staff members to his house for dinner, but the other two felt they had a greater responsibility to the students, and so I went together with the student, neither of us really knowing what to expect.

Having met Mr Ding at the hotel, we took a taxi (at his insistence and expense) to his house, which consisted of two small rooms on the ground floor of a block of old French terraces in the former French concession. The total floor area would have been about 3 metres by 4 metres in the dining room (with beds) and 3 metres by 2 metres in the kitchen (with beds). There was also an outside laundry and shared courtyard, and they shared toilet facilities with several other families. Mr Ding lives there with his wife, his 10-month old baby and his mother in law. They commented that their house is considered slightly larger than average by Shanghai standards. With 6 million people living in the main urban area of 230 square kilometres (compared with Sydney’s 3.3 million living in 4,000 square kilometres), and with very few high-rise buildings, I can believe that space is at a premium. They had no heating, and with an indoor temperature of minus 3 degrees we all happily wore our overcoats, trying to see each other through the steam of our breath.

We enjoyed an excellent evening, certainly a highlight of the trip. We spoke frankly about many things, including China’s one child policy, the Cultural Revolution, religion and politics, China’s image abroad, insurance (and particularly life insurance, a concept which the Chinese find very strange), etc.. Mr Ding’s niece, Ding Hailong, who spoke excellent English, has recently graduated in economics, and I asked her about the kind of training she had received. She replied that Marxist economics was China’s guiding principle, but that Western books were also available as references. I responded by noting some economists seemed to be using the Western books for more than just reference purposes judging by the large numbers of free markets we had noticed. To this she replied “You must understand. Free markets are a legitimate variation within Marxism”, which is not far short of “capitalism is a legitimate form of communism”.

Mr Ding’s wife and mother-in-law spent much of the evening preparing the meal. I lost count of the number of courses served, with food styles from all parts of China. Needless to say, this home cooking was the finest meal we had in China, and this is not to denigrate the superb meals we had throughout our stay. China is perhaps the only nation in the world which can rival France for the quality and variety of its cooking. The remarkable display of hospitality must have cost Mr Ding several weeks wages.

At the end of the meal, he served us coffee (in glasses), and the student who was less subtle than I asked for milk and sugar (not usually part of beverages in China). Mr Ding would have lost face if he could not provide something a guest had asked for, so they set to work to find some sugar (water must have got into it during the summer, as it was frozen solid and had to be chipped away) and some powdered milk, which was mixed up with some hot water (I suspect it may have been the baby’s formula). I’m sorry to say that the Chinese seldom drink milk.

Ding Zhaoqing’s principal occupation is a commercial photographer, specialising in clothes and forklift trucks judging from his scrap book. He is also one of China’s top political cartoonists, and his cartoons have appeared in newspapers and magazines throughout China and overseas. In his spare time, he is a painter, and he presented me with several of his own paintings. Fortunately, I was able to present him with some gifts too, including one of the books I had written and illustrated with my own photographs. At the end of a magnificent evening, he and his niece escorted us back to the hotel via public bus, still trying to grasp the concept of insurance. I hope that I shall have the opportunity to renew this new-found friendship with Mr Ding on a return trip to Shanghai one day, or even in Australia if his wish to work here for a year is fulfilled. The evening was all the more remarkable when it is remembered that less than ten years ago, he could have been arrested for making an approach such as this one he made to a foreigner.

Day 11

Shanghai

Friday, 13 December 1985