Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan 2018

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan 2018

Caucasus 2018

Of course it stands to reason that the weather this morning in Tbilisi should be cold and heavily overcast, with dark grey clouds looming on the surrounding hillsides. After all, the official forecast had been for clear, sunny conditions with temperatures rising to 31 degrees Celsius. With expectations suitably lowered for the day’s photography, we set off from the hotel at 8:50am and headed south to the border between Georgia and Armenia at Sadakhlo-Bagratashen.

On the way out from Tbilisi, we passed through unusually ugly, decaying Soviet prefabricated housing blocks that had been built in the 1970s and many empty factories that had been closed by Georgia’s first President in the immediate aftermath of the breakup of the Soviet Union. It was a disastrous policy that forced mass hunger, unemployment and brought the economy to the brink of collapse. Seeing the housing blocks and disintegrating factory buildings revealed a side of Georgia we had heard about but had not previously witnessed so vividly.

The drive to the border took an hour and ten minutes, passing through agricultural fields with interesting glimpses into Georgian vegetable farming, such as the highly labour-intensive process of picking and packing onions into their distinctive orange bags.

The exit through Georgian immigration was speedy and efficient, and entering the ‘neutral zone’ between the Georgian and Armenian immigration desks we met Aro, the young man who is to be our guide through Armenia. We loaded our bags into the bus, drove 300 metres to the Armenian immigration office, and then unloaded our luggage again because Armenian laws require everyone entering the country to carry their own luggage.

Although most members of the group sailed through Armenian immigration, I and a few others were given a hard time, apparently because we had Azerbaijani stamps in our passports (like everyone in our group). The immigration officer carefully read every stamp on every page in my passport (and I have a 64-page passport with lots of interesting stamps and visas), then did so again for a second time, and then proceeded to ask me where I wanted to go to in Armenia, why I wanted to enter the country, and so on, but was not satisfied with any answers, just shaking his head “no”. I said I was a member of a group, and when he asked where the rest of the group was, I told him (rightly) that they had already been processed and had passed through.

He was VERY unhappy with that answer, but Aro turned up to see what the delay was, and engaged in a long conversation in Armenian, part of which was showing him his phone to confirm I had a hotel booking in Yerevan this evening. In the end, the immigration officer gave me a terrible stamp in the passport (that may well cause me problems when I leave Armenia – maybe his motive!), threw my passport down for me to pick up, grunted and made a hand gesture that suggested sweeping me away from his presence. Aro later explained that they treat some people with Azerbaijani passport stamps in this way as a way of showing support for their own government’s antagonistic policies towards Azerbaijan because of the territorial dispute over the sovereignty of the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh.

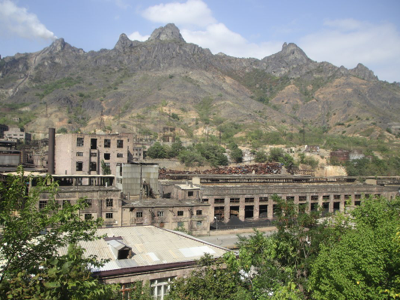

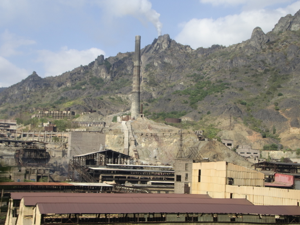

Upon entering Armenia, it was immediately apparent that we had entered a different country. Armenia’s roads were in noticeably worse condition that those of Azerbaijan or Georgia, houses were more run-down, there were more grey concrete Soviet housing blocks, there were far more old Ladas and Volgas on the roads, and there were entire towns of disused factories that were crumbling since their closure at the time of the collapse of the USSR. The entire town of Alaverdi was a spectacular example of this phenomenon. In Soviet times, the town had about half a dozen copper smelters, all of which were highly polluting but they were the backbone of the town’s economy. Today, just one copper smelter remains, still belching out its toxic fumes into the valley, and the rest of the long river bank is filled with the rusting remains of the other factories that are slowly being demolished as local people and help themselves to metal, building materials and anything else that may have value in the abandoned factories.

The border crossing took us an hour and a half, including time to exchange money at the supermarket immediately after the border crossing, and after that we spent 45 minutes to drive to our first stop, the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Haghpat monastery. Founded in 976, the monastery complex contains several churches, a scriptorium, a refectory, several chapels, a well spring, and a number of other buildings that collectively represent a stunning example of Armenian traditional architecture, most of which dates from the 10th to 13th centuries. Standing on the lip of the edge of the Debed Canyon, Haghpat overlooks the river and the surrounding countryside of forests and farmland – unfortunately partially obscured by the thick, white, toxic smoke belching upwards from the remaining copper mine and smelter in Alaverdi. The location of the monastery may have been chosen to protect the peace and seclusion of the monks, but today it is located in a terrible situation from a health perspective – our visit was marred by the strong metallic, slightly headache-inducing smell of the white fume-infused air.

The buildings of the monastery were quite austere compared with the monasteries of Georgia, which were in turn plainer than those in Azerbaijan. There were just a couple f recently restored frescoes and some exquisite carved stonework, but overall, the finish both inside and out was plain, unadorned stone.

After a one hour break for a shared lunch at a riverside restaurant at the bottom of the hill from Haghpat, we began the long drive towards Yerevan, Armenia’s capital city. As the main road was under repair, this meant taking a lesser road that zig-zagged up a steep 300 metre climb to the village of Odzun, giving magnificent views of the countryside. Unfortunately, there won’t be many photos through the bus windows in Armenia as the windows are covered in a dark, highly reflective film that both darkens everything and gives a mirror-like reflectivity unless the combined angles of the sun, bus, window and camera are perfectly aligned – not easy on bumpy, twisting roads. Nonetheless, I have shared some of the few photos I managed to get through the windows to give some idea of Armenia’s beautiful landscapes, even though the reflective film does tend to suck the colour out of any photo.

Our drive continued southwards through the lovely town of Dilijan. Set in beautiful green valleys, the area is often referred to as “Little Switzerland” because of the clean air and mountainous terrain, although I think the Swiss might be affronted if the quality of their roads and houses were compared to those in and around Dilijan. Dilijan is also the location of one of the newer United World Colleges, significant to me as I was Head of the United World Colleges in Hong Kong for seven years. I had heard about the impressive architecture of the environmentally-friendly campus of UWC Dilijan, so it was more than a little exciting to see it from the bus window as we passed by this afternoon. My view wasn’t great as the College was on the right hand side of the bus and I was on the left, and moreover, the heavy grey clouds that had loomed up in the valley made the view through the darkened windows especially gloomy. It would have been lovely to stop and get some photos, but that wasn’t possible as the driver didn’t seem to need a cigarette at the time and we still had a long drive ahead of us.

Turning south from Dilijan, we drove through the 2.5 kilometre ‘tunnel of death’ (so named because the poor ventilation system causes a build-up of fumes, and furthermore the lights inside are turned off during the day – go figure!), and when we emerged we were in a totally different environment. Gone were the steep slopes of bright green grass with forests interspersed between them and dark clouds overhead. Instead, we had gentle slopes, no trees, grasslands and clear sunny skies above us.

We kept driving until we reached the shores of Armenia’s largest lake, Lake Sevan, which takes up one-sixth of Armenia’s territory. It is fed by 28 rivers, but is drained by just one river, the Hrazdan River which drains 10% of the incoming water; the other 90% evaporates.

Until the 1930s, Lake Sevan had been 18 metres higher than it is today. At that time, Soviet authorities decided to lower the level of the lake, partly to create more flat land for farming and partly to provide water for hydro-electric generation. I wondered aloud whether this might explain the lake’s name – as the water level had once been up higher, the inspiration for the name might be Seven-Up (get it?).

Despite its diminished size (it is now about 60% of its previous volume), Lake Sevan remains one of the world’s largest high altitude freshwater lakes. Our specific destination at lake Sevan was Sevanavank, a monastic complex on a high peninsula at the north-west corner of the lake. Sevanavank used to be an island, but with the draining of Lake Sevan it is now connected to the mainland by a wide but low strip of land.

Armenia is famous as the first country to embrace Christianity. It attracted Christian missionaries as early as 40AD, including the apostles Bartholomew and Thaddeus, and in 301 King Trdat III declared Christianity to be the state religion. This required all Armenians to be baptised, and today, about 95% of Armenians regularly attend church services and proclaim themselves to be members of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

Sevanavank dates from the early days of Armenian Christianity. Although the two main churches, Surb Arakelots (Apostles) and Surb Astvatsatsin (Holy Mother of God), date from the relatively ‘recent’ year of 874, it has been suggested that ruins at the top of the hill of the Surb Harutyun may date from as early as 302AD. Surb Harutyun was destroyed in an earthquake in the mid-1000s, by which time the other two churches that still stand today were fully operational. The buildings were constructed from black tuff, which probably gave the monastery its name Sevanavank, which means “the Black Monastery”. Whatever the reason, the churches looked lovely in the last golden rays of sunlight which we managed to get just before the sun dipped below the horizon for sunset.

We left Sevanavank at 7:15pm, and reached our hotel (the Doubletree) in Yerevan about an hour later. Although our bus drove through to the centre of Yerevan where our hotel is located, I can’t say that I’ve seen much of the city yet, as the dark tinted windows obscured most of the night view. I do know that unlike Baku and Tbilisi, Yerevan doesn’t have an old city area as such because all old buildings were destroyed in various earthquakes. Hopefully my curiosity will be satisfied tomorrow as a tour of the city has been scheduled.

Day 11

Tbilisi to Yerevan

Thursday

13 September 2018