Burma 1984

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan 2018

Burma 1984

This morning, we travelled to the south of Bangkok to the “Ancient City”, described as the world’s largest outdoor museum. Covering some 80 hectares of land in the shape of Thailand, it contains replicas of the architectural styles found throughout the country, including reconstructions of many famous buildings which are now in ruins.

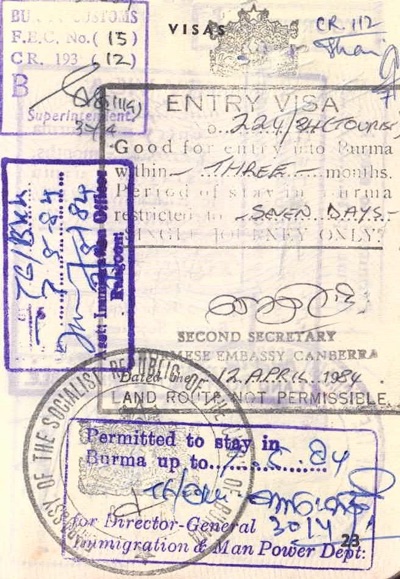

Our ultimate destination for this study tour was, of course, Burma. So, this afternoon, we flew by Thai International Douglas DC-8 (registration HS-TGY, flight TG305) from Bangkok to Burma’s capital city (and its only legal port of entry), Rangoon – although the departure of one student appeared tenuous for a while following the loss of his ticket. Upon arrival at Rangoon’s Mingaladon Airport, we followed the “correct procedures” with the customs officials and thus were able to leave the airport after a “fairly short” three hour period.

I really should expand upon the strange language I have just used.

At the time of our visit, Burma was a strange, idiosyncratic sort of country, controlled by a military government which at the time has been fighting more than 20 different civil wars for almost 40 years against various ethnic groups in the hills around the country’s borders that wanted independence. Because all the land borders were closed because of the fighting, the only way into Burma was by air, and through one airport – Rangoon, the country’s capital city.

On my way to the airport in Bangkok to take the plane to Rangoon, the interpreter said to me “Now, I hope you have the bribes arranged for the immigration officials in Rangoon”. Naturally, I thought he was joking, and I laughed off his comment. But he persisted, and said he had taken several groups into Burma, and claimed that we would be lucky to leave the airport in under 8 hours if we did not pay a bribe to the right person, the official who seemed to be the most senior. He also warned me – don’t give the bribe to the officer who checks the health cards – “he is just a junior officer who has no influence on getting you through the airport”.

I still wasn’t sure if he was serious, so I asked him how much the bribe should be. “Oh, it is never money” came the reply, and then he said “well, for a group of this size of 28 people, I think the right price would be one litre of Johnny Walker Red Label whisky and a carton of 555 cigarettes. You can get them at Bangkok Airport at a good price, as long as all the other passengers going to Burma haven’t depleted the stocks”. Finally, he commented that if I wanted any Johnny Walker or 555 cigarettes for myself, I could buy some at Rangoon Airport as I left the country – they could well be the same ones I had presented when I entered the country.

I was still a bit worried by this, so I discussed the matter with one of the other teachers who accompanied me. And so we agreed – when we arrived and I was satisfied we were speaking to the key person, I would give him the signal, and then he would initiate a little speech, something like “Sir, it is a great honour to be here. We are from Australia and we were exploited the British also as a colonial possession, and so we feel like brothers with you. As a gesture of our brotherly solidarity and deep friendship, we would like to present you with these small gifts for your personal use”. My idea was that that if the official reacted badly to the gift, I could then intervene as the delegation leader and say he was acting contrary to protocol and save the situation –whereas, if I were the person who actually presented the gift and it was the wrong thing to do, then the entire group would suffer. I managed to convince him that his sacrifice would be for the common good of the students.

As we walked across the tarmac in Bangkok to the plane before departure, I couldn’t help noticing that every single passenger was also carrying a bag with whisky and cigarettes. I suspected from this that the advice from the interpreter might be correct, but I was still very unsure.

After a flight of only an hour or so, our DC-8 pulled up in front of an old terminal building in Rangoon bearing a plaque that said it had been built in 1947 by the Calcutta Metropolitan Airports Authority, as an independence gift from the British when Burma gained its independence from British India. The interior of the building had obviously been designed for the climate of Manchester rather than tropical Rangoon, and there was no air conditioning, not that it would have made any difference because the daily afternoon power cut was in force.

An emaciated old man checked the health cards of our group and asked if we had any cigarettes for him. As I replied ‘sorry, no’, I wondered if this would be only airport in the world where a health official would ask for cigarettes! There were no tidy queues in the darkened gloom of the receiving room, just a disorganised mass of arriving passengers, but I found the official who seemed to have the highest rank – I judged this because he had four dragons sewn onto his sleeve, whereas all the others were only 2 or 3 dragon officials.

I approached him with my colleague beside me. After a preliminary look at our papers, his brow began to furrow. “There may be some small irregularities with your documents” he said as he shook his head. I gave my colleague a nudge, and he held up the plastic bag with the whisky and cigarettes. He began to say “Sir, it is a great honour to be here. We are from…” but the official interrupted “Yes, I know all that” and quickly took the parcel and placed it under the bench. The small irregularities with the documents seemed to have disappeared.

We had to pass through quite a number more desks and officers, because the quantity of paperwork to enter Burma is enormous. The customs sheet required arrivals not only to indicate how much cash they had in each currency, but any valuable item such as a camera or jewellery, and even required a statement on the number of rolls of toilet paper, cakes of soap and sticks of deodorant the person had, which was an ominous sign of severe shortages of these things to come during our stay in Burma. Most of the officials asked something like “do you have a small gift for me?” or “may I have my favour now please?”. I gestured towards the senior officer and indicated that we had already given him a small favour. Most of them nodded and proceeded to process our documents, although one went over to the senior officer, who looked across at us, nodded, and indicated for the junior official to continue working with us.

We had been there for almost two hours and were reaching the end of the process. The last officer, a customs official, came over to me and said “Sometimes the procedures here can take many hours, sometimes days. But I can see the boys are tired, and I have been informed that you are good friends of the Burmese people. So instead of checking every item on the customs declaration form, we will just check the cameras today”. As I thanked him for that, he asked the boys to line up against the corrugated iron wall of the customs shed. He asked the boys to hold up their cameras to show him – no, not in front of them, above their heads. He counted. He looked grim. He counted again, and then counted again for a third time.

He still looked worried and came up to me. “Sir, the forms say there are 28 cameras in your group, but I have counted only 23”. I quickly replied that the rest must be in the large suitcases, and he immediately shrugged his shoulders, stamped the forms, waved us out and wished us a happy time in the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma.

The experience at the airport caused me to lead an interesting discussion with the students that evening. Should I have held the moral high ground and resisted the demand to bribe the officials? Maybe, but that would have subjected the boys to many extra hours in the debilitating heat and humidity of an old tropical airport hangar. Did I compromise my own integrity? Maybe, but then again it is important to abide by the customs of other people when you are a visitor in their country, and not impose your own values on their culture. Many moral and ethical situations are not black-and-white. So what should the criteria be to discern the balance of what is appropriate and what is not in situations of ethical dilemma?

In the end, the unanimous consensus in our group was I had acted appropriately because my motive was an unselfish one to help the students in my care, and the alternative would have been to cause them needless suffering.

We drove from the airport south to the port area along the Rangoon River where our hotel was located. Although our arrival was in the early evening, it was immediately obvious that Rangoon provided a clear contrast with the hectic, bustling Bangkok that we had just left. The local people in Rangoon wore traditional dress (the longyi for men), few cars on the roads were newer than late-forties models (and the buses somewhat older than that), and the tallest structures in this city devoid of modern concrete buildings were pagodas!

The city centre (where we were staying) consisted of buildings built by the British in the inter-war period, and there was no evidence of new building (and little evidence of maintenance) since the Japanese Invasion. For the Geographer, Rangoon provided a superb example of Western colonial Influence in an Asian environment.

Monday

30 April 1984

Day 6

Bangkok to Rangoon