I was wrong about league tables

Sunday, 9 January 2011

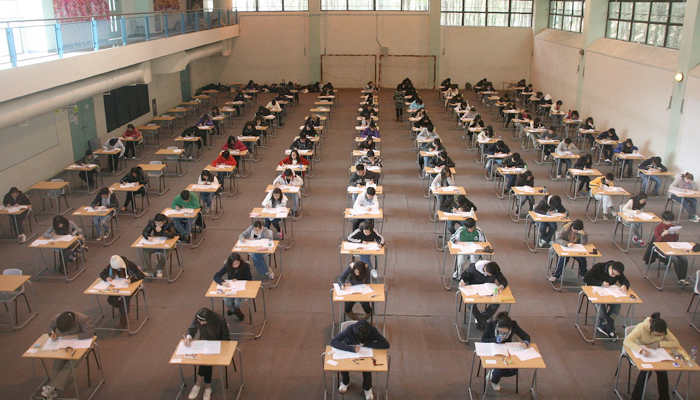

Yesterday, in our Sports Centre, we undertook the aptitude testing for all the Hong Kong students who have applied to enter United World Colleges in September this year. This was the first stage in a selection process that will continue through Challenge Day next month and conclude with panel interviews during March. I helped to supervise the afternoon session, and the pained looks on some of the faces reminded me once again of the enduring truism “no gain without pain”.

Our aptitude testing was introduced last year as a replacement for the Hong Kong Certificate of Education, which was abolished at that time. Our aptitude testing has done more than replace the HKCEE as a selection tool, however - it is also placed all students (regardless of the educational program they are following) on a level playing field in terms of selection, and it has provided us with valuable standardised diagnostic information which can be used to assist students from the first day that they enter their UWC.

In spite of these clear benefits, I have always harbored some doubts about the worth of standardised testing, especially when it is used to compare schools on the narrow basis of examination results through ‘league tables’ in the media.

Back in 2003, when I was working in Adelaide (Australia), I wrote an article in “The Australian Principals’ Newsletter” (http://web.mac.com/scodrington/Site/Print_Downloads_files/League%20Tables_1.pdf) arguing against judging schools purely by their examination results. In that article, I quoted from a letter I had written that was published as that day’s “Boxed Letter” in Adelaide’s main newspaper, “The Advertiser”, in which I wrote (in part):

-

League tables encourage the erroneous idea that the quality of education can be measured simply by examination results. The huge range of achievements, attitudes and values that schools strive to form in young lives cannot be reduced to a simple set of figures to two decimal places.

-

By all means congratulate those students at the top of the list. They were the best on the day and they worked hard under the guidance of fine teachers to get there. Don’t label them the best, though, because that’s not true.

-

There are many other talented and hard-working students who made great efforts, often under challenging circumstances, who are owed as much recognition.

-

I would hate to see our young people’s idealism and zest for life diverted so that they become a spiritless, destructively competitive group of adults. That is the danger of league tables.

-

Education is not a competition. It is a process of enlightenment.

I concluded my article in “The Australian Principals’ Newsletter” by saying:

-

Of course Year 12 examination results are very important. But they are important within the context of a young person’s total formation. Good schools are involved with much more than narrow academic schooling – they are also concerned to provide the best possible opportunities in sport, music, the arts, the development of thinking skills, the formation of spiritual awareness, and meeting each student’s individual needs.

-

League tables may boost the circulation of newspapers, but this should never be done at the expense of placing even more pressure on students to perform, and confusing achievement for effort. Before the media begins to label schools as ‘failures’, perhaps it should look more reflectively at its own responsibilities towards the community it claims to be serving.

But it seems I was wrong, not about the importance of a broad and balanced education, but about the negative the impact of league tables. An article in “The Australian” this week made a strong case that public reporting of school test results lifts student performance, particularly among the poorest and low-scoring schools. (http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/nation/school-league-tables-lift-standards-study-finds/story-e6frg6nf-1225980637161).

The article quoted British research by the Centre for Market and Public Organisation at Bristol University that compared school results in England and Wales. The research found the test scores of Welsh students fell substantially after Wales ceased publishing school performance tables about ten years ago.

As background to the study, school performance tables (commonly known as ‘league tables’) were introduced in Britain in 1992, but abolished by the Welsh Assembly government in 2001 after it was granted power over education policy. This recent research study concluded that the decision to end school league tables "reduced average performance and raised educational inequality". While the results of students in the top 25% of schools were unaffected, the study found that the remainder, particularly the poorest schools with the lowest scores, suffered the biggest drops.

In contrast to Wales, England has continued to publish reports on school performance, which newspapers convert into league tables to rank schools. As a consequence, the English and Welsh education systems are now identical in every way except for the public reporting of school performance through league tables, providing the Bristol University researchers with a natural controlled trial.

The study compared student results in the GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education), taken by Year 11 students in different subjects at the end of the period of compulsory education. The study described the negative impact of the Welsh policy as "sizeable", with the percentage of students achieving at least five good GSCE passes (a C or higher out of A-G) falling by an average of 3.4% per school in Wales after the abolition of the league tables, with the largest drops occurring in the poorest and most disadvantaged schools.

The study also refuted the assertion that school league tables increase social segregation by encouraging parents to leave low-scoring schools for high-performing schools with more affluent students, saying there was no significant impact on sorting students into schools by ability or socioeconomic status.

Having read this study, I confess to feeling somewhat guilty that I argued against league tables so strongly in 2003. As is still the case today, I was then heading a school that was achieving examination results well above the average. If the research was to be believed, my own school’s academic performance would not have been affected one way or the other by the introduction of league tables. However, introducing league tables would have significantly boosted the academic results of students in poorer, under-performing schools.

I feel that this makes my well-intentioned but poorly informed opposition to league tables in 2003 seem somewhat elitist today, hence my feeling of guilt.

Now, having aired my confession publicly, please let me clarify something. Even if standardised tests and league tables do raise school performance, as the research suggests, I will still argue stridently against using the data provided by standardised tests to define the nature and extent of learning or to evaluate teachers.

As Einstein once famously commented, the things that really matter cannot be measured. The fruits of teaching are notoriously difficult to measure, especially by testing that focusses on narrow recall and short-term goals. Those factors that can be measured are often banal in nature and incremental in a spasmodic progression that reflects individual students’ own developmental pathways. It may, for example, take a succession of teachers with a cocktail of different approaches to improve the learning of a poor reader or a struggling maths student. Moreover, there are often significant factors affecting students’ learning that are beyond the control of the teacher, including a range of both genetic and environmental factors.

Effective teaching is therefore a collaborative enterprise, working in partnerships with parents, drawing upon the wide range of skills of a team of dedicated and optimistic teachers who have high expectations of their students’ potential and the persistence to insist that their students rise to those expectations. The two-fold dangers of standardised testing are (1) that this grand enterprise might be reduced in scope to focus only on those few factors that can be measured cheaply and easily on tests, or (2) that the emphasis on gathering data through testing becomes such an important goal that the “testing-tail” wags the “teaching-dog”, eroding students’ educational experiences by intruding into valuable teaching time, thus (paradoxically) reducing test performances.

In that sense, I stand firmly by the words I wrote in 2003 : “Education is not a competition. It is a process of enlightenment.”

One group of students doing our aptitude test yesterday in the Sports Centre