I had to go to Shanghai for a couple of days this week to attend some meetings. Every time I return to Shanghai I am reminded how quickly the city is changing. Four years ago, when my website was in its infancy, I posted a (fairly poorly formatted) gallery of photos taken at that time, together with images taken during my first trip to Shanghai in 1982 to show the contrast - that gallery can be seen HERE.

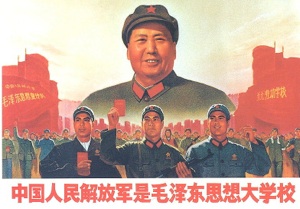

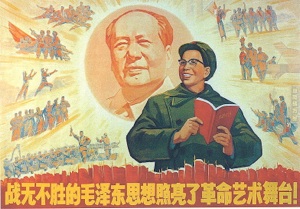

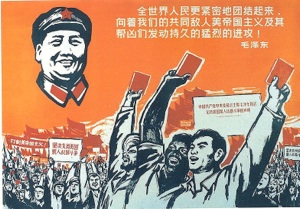

The other opportunity I had for some sightseeing was for a brief a couple of hours on Tuesday afternoon. Unfortunately, the rain on that day was torrential, so a destination under cover was called for. I chose to visit a new gallery displaying the history of China’s propaganda posters (its website is http://www.shanghaipropagandaart.com/). The display was simply amazing - it must have been quite a feat to collect and preserve the posters on display, as most of those from the early period of Liberation and the Cultural Revolution have been shredded long ago for recycling.

While there, I met and had a long conversation with Mr Yang Pei Ming, who is the director of the centre. A softly spoken man with perfect but slow and deliberate English, he has a great passion to preserve what he sees as an important part of China’s recent history, as well as a legitimate and high quality form of artistic expression. We chatted about my own experiences of propaganda art in North Korea, which is perhaps the only place left in the world where the art of propaganda art is still practised. Only a small proportion of the collection of some 5,000 posters is on display in the small gallery, but it was more than enough to keep me fascinated for several hours.

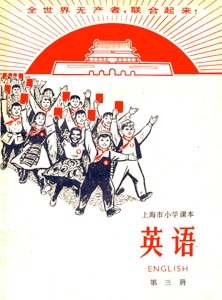

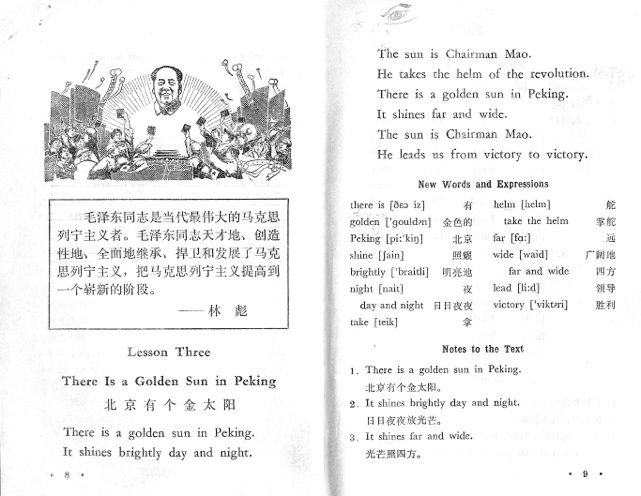

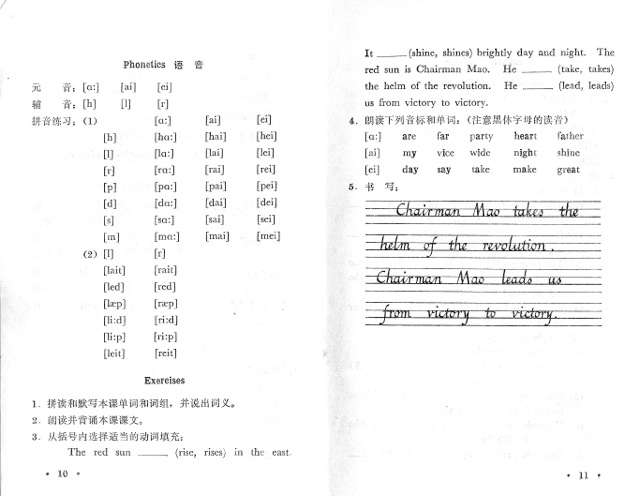

The museum (or gallery might be a more accurate description) has other materials on display in addition to the posters, including Mao statues and busts, and particularly fascinating for me, some English language textbooks from the tumultuous period of the Cultural Revolution. One book published in August 1970 (and costing just 12 fen at the time), was typical of several on display, and opened with the obligatory colour portrait of Chairman Mao, then continuing the same theme with Lesson One. Entitled “Chairman Mao, we wish you a long, long life”, the students were taught the following in English: “Chairman Mao, our Red Commander, we little Red Guards are boundlessly loyal to you. We always remember your teaching: ‘Study well and make progress every day’. From our hearts we wish you Chairman Mao a long, long life!”

Chapter Two continued along similar lines, teaching children about Vice-Chairman Lin Biao’s exhortation to “Study Chairman Mao’s writings, follow his teachings, act according to his instructions and be his good fighters.” (End of Lesson Two!). I’ll bet the children in that classroom had no idea about the interesting turn of events that would befall Lin Biao just 13 months after the book was printed - the events that almost certainly meant the book had an extremely short shelf life.

It would not take long to type out every lesson in English contained in the book, and I am sure you can see the recurring theme of the English language lessons. I have included the entire four pages of content for Chapter Three below for you read for yourself. My visit to the gallery brought me into a world that was much more reminiscent of North Korea than the bustling world of “socialism with Chinese characteristics” (which most foreigners label as capitalism) outside the doors of the gallery. And yet, this was the reality of Shanghai, and indeed all of China, just a few decades ago. It made me wonder what North Korea might be like, could be like, and will be like, three or four decades from now.