From Houston to Sydney 2013

West Africa

2014

Today we seemed to enter another world.

Dogon Country (Le Pays de Dagon), or the territory occupied by the very distinctive Dogon people, is indeed a world apart from the rest of Mali. Located between 60 and 120 kilometres to the east of Mopti along the top and bottom of a high vertical escarpment, Dogon Country is inhabited by people who migrated to the region in the 12th century from south-west of Bamako in order to preserve their animistic beliefs in the face of the advance of Islam. When they arrived, they encountered another ethnic group, known as the Tellem (which means the “found people” in Dogon language), only the archeological remains of whom exist today.

Before driving to Dogon Country, we rose at 7 am, and had yet another bracing cold shower (the hotel’s claims to have hot water available are losing credibility with us now) followed by the simple breakfast of watermelon, paw-paw, a croissant and a piece of French bread – not much gluten free joy here!

The views across the river were magnificent in the morning sunlight, so I took the time to get some photos, and we headed off just after 8:30 am. After stocking up on some bottled water at Sevaré, we took the easy 45 kilometre drive to the village of Songo, located just a few kilometres to the north of the main road between Mopti and Bandiagara.

Songo is famous for its circumcision grotto. Although this Dogon town is all Muslim, the traditional biannual circumcision that is an important component of Dogon culture takes place here at the foot of a high escarpment on the edge of the town.

Andrew and I had visited Songo when we were here ten years ago, but today’s visit was much better. Our previous visit had been somewhat rushed because it was late in the afternoon and the sun was setting, but today we had time to explore the village, see its weavers and builders in action, and experience something of the everyday life of the village before starting the climb to the circumcision grotto.

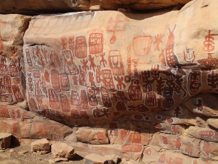

Access to the grotto is only possible for men and women who are not black. A local man showed us the stone where the circumcisions take place (and gave a demonstration of how to sit for the ‘main event’) before explaining the significance of the rock paintings that provide a backdrop to the terrace where the circumcisions are done (these days by a doctor rather than the village blacksmith, who used to perform the task).

Before the circumcision, the boys (aged between 7 and 15) spend 30 days up at the grotto, being initiated into the traditions of the Dogon culture. They spend another 30 days after the ceremony to continue their studies. At the end of the 30 days, they participate in a race down the hill to a particular tree on the plain, and back again to the terrace of the circumcision grotto. The winner of the race gets a supply of food. The one who comes second gets to choose whichever single girl he wants for his wife. The third place getter receives two cows.

We moved on from the circumcision terrace to a cave to the left, where we saw the musical instruments that are only played at the time of the circumcision ceremony, and then the cave where people (adults as well as children) who ‘misbehave’ (i.e. break Dogon law, such as committing adultery) have to sit under a large rock for a period of time before being beaten by a village elder with a large stick. As it was explained to us, “if he dies, then it is all right”.

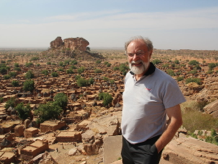

We continued on through the cave, clambering up the rocks to a point where we could enjoy a wonderful panoramic view across the entire village of Songo. It was a magnificent sight, as you can see in the panorama picture at the end of today’s diary.

The surprises continued as we descended from the circumcision grotto. As we neared the bottom of the escarpment, we were greeted by a large group of children from the village who joined together to sing us a welcome song. As we descended further, we passed the meeting house for the village men. It was constructed in the typical Dogon style with a very low roof so that everyone present must remain seated; this is apparently intended so that no-one can stand up and start a physical fight.

After spending an enjoyable and enlightening time in Songo, we returned to the main road and continued east on the sealed road to Bandiagara. Continuing north-east of Bandiagara, the road deteriorated markedly as it degenerated into an unsealed track of alternating sand and bare, rough rock. Our destination was Sanga, a small Dogon town near the edge at the top of the escarpment, and although the distance from Bandiagara was only a few tens of kilometres, the trip was agonisingly slow. Fortunately there were some interesting (but very poor and dry) villages on the way, and the semi-arid terrain was periodically punctuated by the bright green of onion gardens, onions being a major crop for the Dogon people.

We finally reached our hotel, the Campement-Hôtel la Guina in Sanga, at about 1:15 pm. Andrew and I had stayed in this hotel overnight ten years, and my memory of it was that it was very basic (although we only saw it at night, arriving after dark and leaving at dawn the next morning).

My impression of ‘basic’ was confirmed upon our arrival. There was no electricity (the power is turned on at 6 pm each evening and off at 6 am the next day), and the room was so basic that the wardrobe didn’t have any doors or sides left on it. We were first shown to room 6, but we were soon upgraded to room 5 that featured important extras such as a small cake of soap, a toilet roll and a wardrobe with sides and a door. Unfortunately, the lock didn’t work on the door, and we had to be further upgraded to room 4, which was equipped similarly to room 5 (except it lacked a toilet roll, but I brought the one from room 5 with me) and had a lockable door. The shifting of rooms would have all been a bit Monty Pythonesque except that the young hotel manager (who spoke unusually good English) was so embarrassed, so courteous and so apologetic.

We enjoyed a lovely lunch in the hotel dining room comprising some warm bread that the manager had cooked himself, a half chicken (about the size of half an emaciated sparrow, but quite tasty) accompanied by rice and a bowl of minestrone soup to be shared between Andrew and me for the purposes of pouring over our rice – a surprisingly tasty combination.

After lunch, we had about half an hour before we had to meet Mama, so we ventured up to an open third floor terrace at the hotel that provided a wonderful elevated overview of most of the village of Sanga. It was perhaps the most scenic spot in the whole town, with views across to the weekly market on a small knoll to the west of the town, the water well in the centre of town that was a constant focus for villagers’ foot traffic, and the houses with their small granaries punctuated by the massive trunks of huge baobab trees.

We met Mama at 3:00 pm and proceeded to an open space just to the south of the hotel for what promised to be a highlight of the trip – a traditional dance by the Dogon people. This dance lasts about 20 minutes, and is performed periodically as a way to remember dead ancestors. The dancers (all men) wear face masks that symbolise various animals and categories of people – young maidens, warriors, blacksmiths, thieves, snakes, hyenas, cows, evil spirits, and so on, and the dancing is exuberant, energetic, colourful, fast and full of meaning. It was a huge honour for Andrew and me to be welcomed into the audience for the dance, and as you might imagine, I didn’t stop taking photos and video footage (the latter on my mobile phone) during the entire performance. It was mesmerizing, compelling, hypnotic, unforgettable and outrageously photogenic.

When the dancing stopped, the significance of the masks and the dance movements were explained to Andrew and me as guests of the village, after which he had an opportunity to thank the performers and have our photo taken with them.

The dancing may have stopped, but our time exploring Sanga had not. Today was Sanga’s weekly market day (using the Dogon five day week, the normal calendar in this part of the world). So we joined the long line of local people (and several goats) coming and going on a narrow track between the town and the small knoll on which the market was taking place.

I love most traditional markets, and this one was even better than most. It was a riot of colour and activity. Most of the sellers were women, dressed brightly in their “market best” attire, sitting on the ground selling their wares – household goods, crops (with a special emphasis on onions), fruit, noodles, maize paste, spices, cloth, clothes (mostly from China), and lots more. The atmosphere was busy but friendly, with lots of smiles and people passing the time in animated conversations.

As the sun became lower in the sky, we headed back to the hotel, stopping briefly for the obligatory “just have a quick look sir” in the small shops near the hotel entrance. The shops contained a sparse and depressing ensemble of old, dusty wooden masks, broken wooden locks, cracked miniature doors, and cheap jewellery, all of which I found easy to resist to the bitter disappointment of the tourist-starved proprietors.

We arrived back at the hotel at a little after 5:00 pm. There was still an hour to go before the electricity would be turned on, but the interior of our room was already very dark. There was no alternative but to accept the hotel manager’s suggestion of a cool drink in the beautiful garden of the hotel. It was very pleasant to enjoy the cool afternoon breeze and watch the colourful line of people leaving the market knoll, walking along the narrow track through the valley below us.

The hotel might lack electricity (and of course internet), but the atmosphere and the warmth of the hospitality more than compensated. Andrew and I had a spaghetti and beef dinner on the outside terrace of the hotel, and were pleased to see that unlike our recent stays in Segou and Mopti, we were not the only guests in the hotel – this time we are sharing the hotel with an elderly French couple.

I guess the recovery of Mali’s tourism industry has to begin with small steps. Dogon Country is an excellent place for it to start – although not easily accessible and lacking infrastrcture, it is safe, secure, hospitable, and very importantly, distinctively unique.

Day 12 - Mopti to Dogon Country

Wednesday

8 January 2014